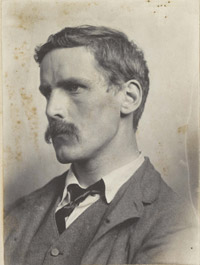

Thomas Graham Balfour – Cousin

“He was inexhaustible, he was brilliant, he was romantic, he was fiery, he was tender, he was brave, he was kind”

(Thomas Graham Balfour, The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson, vol ii [London: Methuen, 1901], p. 185)

Thomas Graham Balfour (1858-1929) was RLS’s cousin and biographer. He was also an educationist. Balfour was born to Thomas Graham Balfour (senior) and Georgina Prentice. Balfour married Rhoda Brooke in 1896 and the couple had two sons. Balfour lived in Vailima with the Stevenson family during the last two and a half years of RLS’s life.

He is particularly significant because of his biography on RLS, The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson (1901).

While critics see this as a well-written and useful account of RLS’s life, the work has also been negatively assessed. For example, some authorities argue that Fanny was able to assert too much authorial control over the biography. Indeed, Sidney Colvin originally wished to complete the biography, but disputes with Fanny led him to drop the project.

Further Reading:

Balfour, Thomas Graham, The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson, 2 vols (London: Methuen, 1901)

Alison Cunningham

“Lew came home from the English Church in a great way, because, he said, the minister was preaching against Presbyterianism. No wonder he was angry! ‘What,’ said Lew with some warmth, ‘an English clergyman preaching against a Church for which our forefathers have bled and died! How dare he!’ So dear Lew did not go back to the church in the afternoon.”

(Alison Cunningham, Cummy’s Diary: A Diary Kept by R.L. Stevenson’s Nurse Alison Cunningham While Travelling with Him on the Continent during 1863 (London: Chatto & Windus, 1926), p. 87)

Alison Cunningham, “Cummy” (1822-1913), was RLS’s nurse. Born in Torryburn, Fife, Cummy was a strict Calvinist. She became RLS’s nurse in 1852, remaining in the household until November 1872. She was deeply devoted and loyal to the Stevensons and loved RLS.

Cummy’s religious views had a strong influence on the young Stevenson: “if Louis spent, as he tells us, ‘a Covenanting childhood’, it was to Alison Cunningham that this was due.

“Besides the Bible and the Shorter Catechism, which he had also from his mother, Cummie filled him with a love of her own favourite authors, McCheyne and others, Presbyterians of the straitest doctrine. [. . .] In matters of conduct, Cummy was for no half-measures. Cards were the Devil’s Books. [. . .] The novel and the playhouse were alike anathema to her; and this would seem no very likely opening for the career of one who was to be a novelist and write plays as well. For her pupil entered fully into the spirit of her ordinances, and insisted on a most rigorous observance of her code”

(Graham Balfour, The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson [London: Elibron, 2005], pp. 30-31).

Recent critics have suggested that Cummy’s relationship with RLS was problematic – for example, that her religious views were damaging to his health, his ill and feverish imagination turning religious stories into nightmares. But her religious views probably also inspired Stevenson, sparking the beginnings of ideas for what he would later write. Perhaps, though, this strict Christianity also influenced RLS’s decision in his early twenties to abandon the Christian faith (a decision which particularly hurt his father).

Stevenson was very fond of Cummy. He dedicated A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885) to her to thank her for the nights she spent caring for him when he was ill as a child:

To Alison Cunningham From her Boy

For the long nights you lay awake

And watched for my unworthy sake:

For your most comfortable hand

That led me through the uneven land:

For all the story-books you read:

For all the pains you comforted:

For all you pitied, all you bore,

In sad and happy days of yore: –

My second Mother, my first Wife

The angel in my infant life –

From the sick child, now well and old,

Take, nurse, the little book you hold!

And grant it, Heaven, that all who read

May find as dear a nurse at need,

And every child who lists my rhyme,

In the bright, fireside, nursery clime,

May hear it in as kind a voice

As made my childish days rejoice!

(Robert Louis Stevenson, A Child’s Garden of Verses [New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1895], p. ix).

Indeed, Cummy’s diary (Cummy’s Diary, preface by Robert T. Skinner [London: Chatto and Windus, 1926]), which she kept when the Stevensons travelled in Europe in 1863, gives a valuable insight into the kind of woman she was. The diary shows that she had a sense of humour and was preoccupied by issues like religious and national difference.

After Stevenson’s death, Cummy attracted some celebrity. A Child’s Garden of Verses had become increasingly popular in the early twentieth century. Many people wanted to meet the woman who had inspired and nursed RLS. Cummy seemed to enjoy the attention, delighting in talking about her time with Stevenson.

Alison Cunningham died at the age of 92.

Katharine de Mattos – Cousin

“I am sick to death of the matter and the notion of any quarrel has made me feel quite ill. It is of course very unfortunate that my story was written first and read by people and if they express their astonishment it is a natural consequence and no fault of mine or any one else. I assume that you know me sufficiently to be sure that I have never alluded to the matter even to friends who have spoken of ‘The Nixie’. I trust this matter is not making you feel as ill as all of us.

Yours affectionately, Katherine De Mattos”

(Letter from Katherine De Mattos to RLS, early April 1888. From The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol vi [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 169)

Katharine Elizabeth Alan Stevenson de Mattos (1851-1939) was RLS’s cousin and Bob Stevenson’s sister. She was born to Alan Stevenson and Margaret Scott Jones. She married William Sydney de Mattos (b. 1851) and the couple had two surviving children. Katharine became an author, writing under the pseudonym of Theodor Hertz-Garten.

RLS and Katharine played together when they were children, and she visited the Stevensons’ home in Bournemouth.

Katharine had a close relationship with RLS (who dedicated Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde to her). Then, in March 1888, they quarreled after Fanny Stevenson published the short story “The Nixie”. W.E. Henley accused Fanny of plagiarizing the story from Katharine’s own. RLS took his wife’s side, hurting Katharine’s feelings and alienating himself from Henley.

Samuel Lloyd Osbourne – Stepson

“I had grown to love Luly Stevenson, as I called him; he used to read the ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ and the ‘Tales of a Grandfather’ to me, and tell me stories ‘out of his head’; he gave me a sense of protection and warmth, and though I was far too shy ever to have said it aloud, he seemed so much like Greatheart in the book that this was my secret name for him”

(Lloyd Osbourne, An Intimate Portrait of RLS, [New York: Charles Scribner’s and Sons, 1924], pp. 2-3)

Samuel Lloyd Osbourne (1868-1947), known as Lloyd, was RLS’s step-son. He was born in San Francisco to Samuel and Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne. Lloyd went with his mother and sister Belle to Europe when they were pursuing their art studies. In 1876 when they went to Grez, the family met RLS.

After the marriage of his mother and RLS, Lloyd accompanied the Stevensons on many of their travels, settling with them at Vailima. He and his sister Belle wrote about RLS and their experiences in Samoa in Memories of Vailima (1902). Lloyd also wrote about RLS in An Intimate Portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson (1924).

During a rainy holiday in Scotland when Lloyd was twelve, he and RLS drew a map, which inspired Stevenson to write Treasure Island (1883). He dedicated the novel to his stepson. Lloyd and RLS collaborated on The Wrong Box (1889), The Wrecker (1892) and The Ebb-Tide (1894), although critics have debated on the extent and importance of Lloyd’s contributions.

After RLS’s death, Lloyd continued to write, although he was not very successful. He published more than a dozen novels, for example Baby Bullet: The Bubble of Destiny (1905), Three Speeds Forward: An Automobile Love Story with One Reverse (1907), and Peril (1929). Wild Justice (1906) is a collection of short stories about Samoa.

Lloyd married his first wife, Katharine Durham, in Honolulu in 1896. The couple had two children, Alan and Louis, and divorced in 1914. In 1897, Lloyd became the American Vice Consul in Samoa to the United States. In 1916, he married and divorced again. In 1936 he had a son, Samuel, with Yvonne Payerne, a young woman he’d met in France.

In 1941 Lloyd returned to America and died in California in 1947.

Further Reading:

Hirsch, Gordon, ‘The Fiction of Lloyd Osbourne: Was This “American Gentleman” Stevenson’s Literary Heir?’, Journal of Stevenson Studies 4 (2007), pp. 52-72

After Stevenson’s death, Osbourne published thirteen volumes of fiction, including four collections of short stories. Some of his work is embarrassing to read today, such as the numerous stories of a rich heiress pursued and won by a hardworking young American man, many of them unpleasantly snobbish and revealing traces of racism. The mystery/adventure novels with elements of comic absurdity (The Adventurer, 1907, and Peril, 1929) are more interesting, reminiscent in ways of The New Arabian Nights, The Wrong Box and The Wrecker. It was, however, in the short fiction set in the South Seas (The Queen against Billy, 1900, and Wild Justice, 1906) that Osbourne has most affinities with Stevenson. The stories can be grouped in four categories: (i) those about relationships between Euro-American men and native women, (ii) those about exploitative and lawless non-native incomers, (iii) stories with native narrators and their reactions to imperialist intrusion, (iv) stories of moral complexity in situations of multicultural contact. The best of these reflect Stevenson’s influence and “represent an achievement comparable to the Stevenson-Osbourne collaborations” [Hirsch, p. 69]

Osbourne, Lloyd, An Intimate Portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson (New York: Charles Scribner’s and Sons, 1924

Strong, Isobel and Lloyd Osbourne, Memories of Vailima (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1902) and (London: Archibald Constable & Co, 1903) [The US edition is 228 pp. with 31 black and white photographs; the UK edition is 151 pp and with only an engraved portrait frontispiece.]

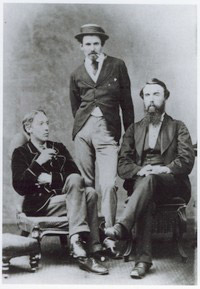

Bob Stevenson – Cousin

“What was our dismay, in the midst of quite a crowd of the gay world, to see that open cab, at a word of command from Robert Louis, draw near the pavement as we approached, when two battered straw hats were lifted to us with quite a Parisian grace. Both [Bob and Louis] wore sailor hats with brilliant ribbon bands, both were attired in flannel cricketing jackets with broad bright stripes, and round Louis’s neck was knotted a huge yellow silk handkerchief, while over both of their heads one of them held an open umbrella. [. . . ] such an apparition in the open cab required more courage to face than perople accustomed to the present-day use of tennis garb can easily imagine. [. . . ] And when we described that startling vision that was slowly creeping along Princes Street in the open cab, [Mrs Stevenson] laughed till her tears fell”

(Margaret Moyes Black, Robert Louis Stevenson, [Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, 1898], p. 63)

Robert (Bob) Alan Mowbray Stevenson (1847-1900) was Stevenson’s cousin and lifelong friend. He was born in Edinburgh to Alan Stevenson and Margaret Scott Jones.

An aspiring artist, Bob studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Antwerp in 1873. During the 1870s, he became part of the communities of artists working in Fontainebleau and Barbizon. RLS often visited him, and of the two cousins it was Bob who first met Fanny and Belle Osbourne (who he admired).

In 1881, Bob married Harriet Luisa Purland and the couple had a son in 1894. Unfortunately, Bob had little success as a painter, but gained a strong reputation as an art critic.

Bob and RLS first became friends when Bob was studying at Edinburgh Academy and living at Inverleith Terrace with RLS and his parents. They later cemented their friendship in 1871, when Bob returned to Edinburgh to live with his widowed mother.

RLS and Bob were both members of the Speculative Society at Edinburgh University. They were also members of the LJR (Liberty, Justice, Reverence) League, a club founded with friends like Charles Baxter in a pub in Advocate’s Close, Edinburgh. The club’s tenet was “disregard, everything our parents taught us”, a sentiment Thomas Stevenson found deeply upsetting. Indeed, RLS’s father disapproved of Bob, blaming him for his son’s lack of religious faith.

Nevertheless, RLS and Bob had a strong relationship which was marred by a quarrel between RLS and W.E. Henley in March 1888. The quarrel was over a story Bob’s sister, Katharine de Mattos, had written. According to Henley, a story Fanny published, “The Nixie”, was plagiarized from Katharine’s original story. Bob took the side of his sister and Henley, and his relationship with RLS suffered. Bob may also have felt embarrassed about the fact that RLS had been helping to support him, sending him £40 a year from 1887. In addition, in 1881 Bob married Harriet Purland; in a Letter of 1888, RLS says “Two of [my old friends] have married wives who love me not” and the editor supposes that this refers to Bob and Simpson (Letters , ed. Booth and Mehew, vol 6, p. 135 and n.). However, towards the end of RLS’s life, the two exchanged more congenial letters.

Bob is apparently the model for Peter Van Tromp in “The Story of a Lie” (1879, where in “the gaudiest cafés” of Paris “he might be seen jotting off a sketch with an air of some inspiration”), for “The Young Man with the Cream Tarts in New Arabian Nights (1882, dedicated to Bob), for Paul Somerset in ‘“Edifying Letters of the Rutherford Family” (probably written 1876-7) and again in The Dynamiter (1885), the Prince in Prince Otto (1885) and Stennis ainée in The Wrecker (1892). Indeed, Fanny Stevenson says “whenever my husband wished to depict a romantic, erratic, engaging character, he delved into the rich mine of his cousin’s personality” (“Prefatory Note”, New Arabian Nights, Tusitala Edition, p. xxviii).

The people who knew Bob considered him to be extraordinarily intelligent, a fascinating and engaging character who unfortunately was unable to achieve his artistic goals. In “Talk and Talkers: I”, RLS calls Bob “Spring-Heel’d Jack” and praises “the insane lucidity of his conclusions, the humourous eloquence of his language” (“Talk and Talkers I”, in Memories and Portraits, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol ix [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911], p. 87).

Further Reading:

Lubren, Nina, Rural Artists’ Colonies in Europe 1870-1910 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001) [Contains a fair bit of detail about Bob, RLS et al in Barbizon and Grez-sur-Loing.]

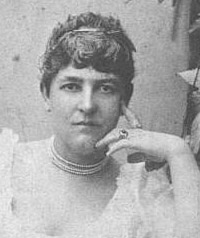

Frances (Fanny) Van de grift Osbourne Stevenson – Wife

“I wandered away from Louis, gathering shells, but was recalled by a wild shout. I found Louis bending over a piece of the outer reed that he had broken off. From the face of both fractures innumerable worms were hanging like a sort of dreadful, thick fringe. The worms looked exactly like slender earthworms, more or less bleached, though some were quite earthworm colour. They lengthened out and contracted again until I felt quite sick and had to fly from the sight.

Afterward, Louis broke other pieces of rock; one kind always contained worms; another kind, lighter in colour and firmer in texture, contained much fewer worms, also empty holes in the process of closing up; still others were close and hard and white, like marble. I got a good many shells, and after a fruitless search for some other way across the island than round the inland lagoon, I gave it up and we retraced our footsteps; that is, for a certain time, when we became lost, or as Louis indignantly put it: ‘Not lost at all; we only could not find our way.'”

(From the diary of Fanny Stevenson, 21 May 1890, The Cruise of the Janet Nichol: Among the South Sea Islands, A Diary by Mrs Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Roslyn Jolly [Sydney: University of New South Wales Press Ltd, 2004], p. 122)

Frances (Fanny) Matilda Van de Grift Osbourne (1840-1914) was RLS’s wife. She was born in Indianapolis to Jacob Vandegrift and Esther Thomas Keen.

In 1857, Fanny married Samuel Osbourne. The couple had three children: Isobel (Belle), born in 1858, Samuel (Lloyd), born in 1868, and Hervey, born in 1871. Sadly, Hervey died in 1876 after a long illness.

Fanny and Sam had a turbulent married life. They moved frequently within the US, and were often separated while Sam tried to make his fortune. Sam was often unfaithful and in 1875, Fanny left him.

She took the children to Europe where she and Belle pursued their art studies. In 1876 they arrived in Grez and it was here that she met RLS. A year later, Fanny and RLS had become close, and perhaps romantically involved, but in 1878, Fanny and the children returned to her husband in California.

Against the wishes of his friends and family, RLS resolved to pursue Fanny. In 1879 he traveled by train across America to California (he later described this journey in The Amateur Emigrant [1895]). Fanny divorced Sam, and she and RLS were married in San Francisco in May 1880. The couple honeymooned in Napa Valley and RLS later wrote about this in The Silverado Squatters (1884).

Although at first RLS’s parents disapproved of the marriage, they came to love Fanny and welcomed her as part of the family. RLS’s friends, however, were not persuaded, and many never came to like her. Several disapproved of the fact that Fanny was ten years older than RLS and married when he met her, but they also disliked her mannerisms and influence on RLS. She was also fiercely protective of RLS’s health and discouraged friends from visiting when he was unwell. This interference was often resented and the marriage put a strain on many of RLS’s friendships.

Literary critics and biographers have also shown keen animosity towards Fanny, suggesting she took too much control over his life and writing. Fanny was, however, very proud of her husband’s work and collaborated with him on The Dynamiter (1885). She also claimed to have told RLS to rewrite an early draft of Jekyll and Hyde (1886) to make it the masterpiece it is today – however, there is no proof that this was the case.

Nevertheless, it seems clear that RLS valued his relationship with his wife. He dedicated Weir of Hermiston (1896) to her, thanking her for all of her help. His poem “My Wife”, is perhaps a telling description of RLS’s feelings for Fanny:

Trusty, dusky, vivid, true

With eyes of gold and bramble-dew

Steel-true and blade-straight

The great artificer

Made my mate.

Honour, anger, valour, fire;

A love that life could never tire;

Death quench or evil stir,

The mighty master

Gave to her.

Teacher, tender, comrade, wife,

A fellow-farer true through life,

Heart-whole and soul-free

The august father

Gave to me.

From Songs of Travel, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol xiv (London: Chatto and Windus, 1911), pp. 235-36.

After RLS’s death in 1894, Fanny, Belle and Lloyd stayed at Vailima for a few months.

For the next couple of years, Fanny lived in various places in California and Hawaii, and travelled to Europe. She settled in Santa Barbara, CA in 1908. From her house, “Stonehenge”, she worked on the publication of the journal she kept on board the Janet Nicholl.

Fanny had two significant relationships after her husband’s death. Her first was with Gelett Burgess (1866-1951), who had designed the bronze panels for RLS’s tomb. Her second was with Edward (Ned) Salisbury Field (d. 1936), a journalist who was her companion and secretary until her death in 1914. Just six months later, Belle married Ned Field and together they took Fanny’s ashes to be buried with RLS’s.

Further Reading:

Fanny and Robert Stevenson: Our Samoan Adventure, ed. by Charles Neider (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1956) [Introductory texts by RLS and Fanny Stevenson, including Fanny’s diary from 1890-93.]

Fitzpatrick, Elayne Wareing, A Quixotic Companionship: Fanny and Robert Louis Stevenson, 2nd edn (Monterey: Old Monterey Preservation Society, 1997). [104 pages. Illustrated and available only through the COOPER STORE operated by Old Monterey Preservation Society on Alvarado Street, Monterey, CA, 93940. Tel: (+001) 831 649 7111.]

Forster, Margaret, Good Wives? Mary, Fanny, Jennie and Me, 1845-2001 (London: Chatto, 2001). [Includes a section on Fanny Stevenson as a wife.]

Hinkley, Laura, The Stevensons: Louis and Fanny (New York: Hastings House, 1950)

Hubbard, Elbert, Robert Louis Stevenson and Fanny Osbourne (East Aurora, NY: Roycrofters, 1906)

Jolly, Roslyn, “Women’s Trading in Fanny Stevenson’s The Cruise of the Janet Nichol”, in Economies of Representation, 1790-2000: Colonialism and Commerce, ed. by Leigh Dale and Helen Gilbert (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), pp. 143-55.

[A comparative study of the pragmatics of interaction in four trading encounters on South Sea islands involving Fanny Stevenson and the rhetoric of her narratives of them in Janet Nichol. Two involve failed communication, at Marakai (Gilbert Islands) and Penrhyn (Cook Islands), where Fanny observes apparent greed, uncivilized behaviour, suspicion and irrational hostility – which she does not try to relate to the inhabitants’ experience of being cheated by white traders, their incomprehension of money-based interactions and their fear and undying resentment of the depredations of duplicitous slave-traders. Two later encounters are more successful, at Natau and Nanoma (Ellice Islands): here Fanny interacted on board ship and with women in undefined trading/gift-giving transactions involving mutual respect. She has also now learnt to understand the fears and lack of trust of the natives. In depicting the native women ‘taking possession’ of her and treating her as a pet she inverts roles assigned by typical imperial narratives. At the same time, her narrative ensures her an ultimate controlling power to interpret and judge.]

Lapierre, Alexander, Fanny Stevenson (Paris: Robert Lafont, 1993). English translation: Fanny Stevenson: Muse, Adventuress & Romantic Engima (Fourth Estate, 1995).

– – – , Fanny Stevenson: Entre passion et liberté (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1993).

[Portrays Fanny as an adventurous woman even without RLS’s influence. Inserts a large number of fictionalized narrative scenes. See also Jean-Pierre Naugrette, Studies in Scottish Literature 28 (1993), pp. 250-53.]

Lucas, E.V., The Colvins and Their Friends (London/New York: Methuen/Scribner’s, 1928).

[Includes several chapters on RLS and quotes many letters from Fanny Stevenson to Colvin and Fanny Sitwell.]

Mackay, Margaret, The Violent Friend (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1969)

– – – , The Violent Friend: The Story of Mrs Robert Louis Stevenson (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1968) Also an abridged edition (London: J.M. Dent Sons Ltd., 1970)

Sanchez, Nellie Van de Grift, The Life of Mrs Robert Louis Stevenson (New York/London: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1920).

[Favourable portrait by Fanny’s sister; contains details of her early life not found elsewhere.]

Stevenson, Fanny, The Cruise of the Janet Nichol (London/New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1915).

[The diary on which this is based is in the Silverado Museum.]

– – – , The Cruise of the Janet Nichol among the South Sea Islands. A Diary (London: Chatto & Windus, 1924).

– – – , Stevenson, Fanny Van de Grift , The Cruise of the “Janet Nichol” among the South Sea Islands, ed. by Roslyn Jolly (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2003). Also University of Washington Press, 2004.

[The text of the 1890 diary as revised by Fanny for publication in 1914, with the addition of a substantial introduction plus explanatory notes and recommended reading. Illustrated with photographs taken on the cruise, some previously published in the 1914 edition, many published here for the first time. German translation published as Kurs auf de Sudsee: Das Tagebuch der Mrs Robert Louis Stevenson (Munchen: Frederking & Thaler, 2005).]

Margaret Isabella Balfour Stevenson – Mother

“Place of Birth: 8 Howard Place, Edinburgh.

Time of Birth: Wednesday, 13th November, 1850 at 1:30 p.m.

Color of Eyes: Blue at first turning to hazel.

Color of Hair: Very fair almost none at first.

Nurse’s name: Mrs Sayers.

Doctor’s name: Dr Malcolm

Surname: Stevenson

Christian Names: Robert Louis Balfour

Pet Names: Boulihasker, Smoutie, Baron Broadnose, Signor Sprucki, Maister Sprook and many others, but Smoutie stuck to him until he was about 15”

(Margaret Isabella Balfour Stevenson, Stevenson’s Baby Book: Being the Record of the Sayings and Doings of Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson, Son of Thomas Stevenson, C.E., and Margaret Isabella Balfour or Stevenson [San Francisco: Printed for John Howell by J.H. Nash, 1922], p. 9)

Margaret Isabella Balfour Stevenson (1829-1897) was RLS’s mother. She was 1 of 13 children born to the Reverend Lewis Balfour, the minister of Colinton, and Henrietta Scott Smith. RLS often visited Colinton (which was then a separate village just beyond Edinburgh and is now within the city) as a child.

“Maggie” (as she was known to her family) married Thomas Stevenson in 1848 and gave birth to RLS in 1850. She had a strong and loving relationship with her son. Although quarrels between RLS and his father about religion, his career and his marriage were upsetting to the family, the family remained close.

After her husband died in 1887, Maggie went with RLS and Fanny on their travels to America and the South Seas and even settled with them in Vailima. She returned to Edinburgh to live with her sister after RLS died.

Further Reading:

Sandison, Alan, ‘The Shadow of Jocasta: Margaret Stevenson & Son’, Rivista di Studi Vittoriani 20 (2007), pp. 31-54. This was a special Stevenson number of the journal.

[Stevenson never shook free from his mother. Rivalry over her (“my mother is my father’s wife”, 1875) possibly partly motivated the 1873 rows with his father. Only a few weeks after his father died he insisted that his mother accompany him and family to America and then to the South Seas. Margaret Stevenson was actually delighted by the challenge of backwoods and South Sea islands. An attempt to show independence by writing an account of their travels was discouraged by RLS, so her lively From Saranac to the Marquesas was not published until 1903. Letters from Samoa (1906) is a greater literary achievement (and reveals how much of the creation of Vailima came from her—she encouraged and paid for the new wing, for example).]

– – – Stevenson’s Baby Book: Being the Record of the Sayings and Doings of Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson, Son of Thomas Stevenson, C.E., and Margaret Isabella Balfour or Stevenson(San Francisco: Printed for John Howell by J.H. Nash, 1922)

– – – From Saranac to the Marquesas and Beyond, ed. by Marie Clothilde Balfour (London: Methuen, 1903)

[Letters written to her sister Jane Whyte Balfour from 1887-88.]

– – – ‘Notes about Robert Louis Stevenson from his mother’s diary’, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson,Vailima edn, vol xxvi (New York/London: Scribner’s/Heineman, 1923)

[Year-by-year summary 1850-88 from Margaret’s own diaries, prepared by her in 1895-96.]

Stevenson, Margaret Isabella, Letters from Samoa: 1891-1895, ed. and arranged by Marie Clothilde Balfour (New York: Charles Scribner’s & Sons, 1906)

Thomas Stevenson – Father

“The book has the same fault as the Inland Voyage for there are some three or four irreverent uses of the name of God which offend me and must offend many others. They might have been omitted without the slightest damage to the interest or the merit of the book. So much for your absurdity in not letting me see your proof sheets. The only other fault in the book is, I think, a superfluity in the way of description of scenery. Had there been a great variety of scenery the objection would not have been justifiable but when the scenery is so generally the same I think some of it might have been spared. On the whole however I think it is a very successful volume of travel and I believe that your two volumes are unique in point of style”

(Thomas Stevenson in a letter to RLS 8 June 1879, discussing Travels with a Donkey. From Robert Louis Stevenson: The Critical Heritage, ed. by Paul Maixner [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 64)

Thomas Stevenson (1818-1887) was RLS’s father. Thomas followed in his father Robert Stevenson’s (1772-1850) footsteps, becoming a lighthouse engineer in the family firm. He designed more than thirty lighthouses.

Thomas was a Scottish Calvinist, and a firm believer in the importance of the Christian faith. He married Margaret Isabella Balfour in 1848, and two years later, RLS was born.

Thomas had a strong bond with his son, despite quarrels over religion, RLS’s refusal to become an engineer or to continue law professionally, and RLS’s decision to marry Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne. Despite his initial unhappiness, Thomas developed a good relationship with his daughter-in-law and he and Stevenson remained close throughout his life.

RLS wrote about his father in the essay “Thomas Stevenson, Civil Engineer” for The Contemporary Review in 1887. The essay was later included in Memories and Portaits (1887).

Further Reading:

Bathurst, Bella, The Lighthouse Stevensons (London: Harper Collins, 1999)

Leslie, Jean and Paxton Roland, eds, Bright Lights: the Stevenson Engineers 1752-1971 (Edinburgh: Jean Leslie and Roland Paxton, 1999)

[126 illustrations (black and white and colour). Produced on the occasion of the “Stevenson Family of Engineers Symposium” held at the Royal Museum of Scotland in 1994. Family recollections by Jean Leslie, grand-daughter of Charles Stevenson, and professional comment on engineering aspects of the Stevenson lighthouses by Professor Roland Paxton. Includes a chapter on Robert Louis Stevenson’s life as a reluctant trainee engineer together with his own account of the night-time stagecoach journey south after working at Wick breakwater. Now out of print, but copies usually available through AbeBooks.com]

Villa, Luisa, “Quarreling with the Father”, in Robert Louis Stevenson: Writer of Boundaries, ed by Richard Ambrosini and Richard Dury (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006), pp. 109-20

Belle Strong – Stepdaughter

“Louis and I have been writing, working away every morning like steam-engines on Hermiston [. . . ]. ‘Belle,’ he said, ‘I see it all so clearly! The story unfolds itself before me to the last detail – there is nothing left in doubt. I never felt so before in anything I ever wrote. It will be my best work; I feel myself so sure in every word!'”

(Belle Strong, taken from a journal entry for 24 September 1894 and included in Memories of Vailima, by Isobel Field and Lloyd Osbourne [New York: Scribner’s, 1902], pp. 96-97).

“She is my wife’s daughter, my secretary, my amanuensis, my woman-Friday on my desert island, my finder of things, my last assistance, my oasis, my staff of hope, my grove of peace, my anchor, my haven in a storm. She’s Belle, I suppose”

(Robert Louis Stevenson, from An Object of Pity, jointly written by Stevenson, his family and friends as a joke [privately printed in Sydney in 1892], quoted in Stuart Campbell RLS in Love [Dingwall: Sandstone Press, 2009], pp. 41-42).

Isobel (Belle) Osbourne (1858-1953) was RLS’s step-daughter. She was born in Indianapolis to Samuel and Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne.

Both Belle and her mother were interested in art and became art students in Paris. In 1876 Belle, her brother Samuel (Lloyd) Osbourne and Fanny went to an art colony in Grez, France, where Fanny met RLS.

Belle married the artist Joseph Strong (1853-1899) in 1879 and gave birth to a son, Austin Strong (1881-1952). In the 1880s, the Strongs lived first in San Francisco (where they helped give a memorable studio party for Oscar Wilde in the spring of 1882). and Joe Strong came up to stay with the Stevenson party in Silverado and Calistoga where he drew pictures of the miners’ cabin and proved “a most good-natured comrade and a capital hand at an omelette”. In 1882 they went to Hawaii. The Stevensons met up with them there when the Casco arrived in Honolulu in January 1890. Joe Strong had a drink problem and was not an ideal husband; trying to help, RLS took him on the Equator cruise as photographer (July-December 1889, ending in Samoa) and sent Belle and Austin to Sydney with a small allowance. Belle later joined Stevenson at Vailima in May 1891, where she became his valued “amanuensis”, transcribing his fiction to dictation when he was too ill to physically write himself. She and her brother Lloyd wrote about RLS and their experiences in Samoa in Memories of Vailima (1902).

Joe also came to Vailima in May 1891, but his irregular life caused problems. Belle finally divorced him in 1892. In 1914, she married her mother’s secretary (and possibly lover), the journalist Edward (Ned) Salisbury Field (d. 1936) just six months after Fanny died. Together, Belle and Ned took Fanny’s ashes to Mount Vaea, where RLS was buried. In the 1920s the Fields became rich after they found oil on their land. Belle wrote her memoirs in This Life I’ve Loved (1937).

Belle’s son Austin went on to become a playwright, writing successful Broadway plays such as Drums of Oude (1955) and Seventh Heaven (1922-24).

Further Reading:

Bolitho, Hector, Haywire: An American Travel Diary(New York: Longmans, Green, 1927)

[RLS is mentioned in pages 111-13 in connection with his step-daughter, Isobel Field.]

Field, Isobel, A Bit of My Life (Santa Barbara, CA: Schauer Printing Studio, 1951)

– – – , This Life I’ve Loved (London/New York: Longman, Green/Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1937)

[‘Gossipy and attractive memoirs’ by RLS’s stepdaughter; also listed as published by Michael Joseph.]

Strong, Isobel and Lloyd Osbourne, Memories of Vailima (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1902) and (London: Archibald Constable & Co, 1903) [The US edition is 228 pp. with 31 black and white photographs; the UK edition is 151 pp and with only an engraved portrait frontispiece.]