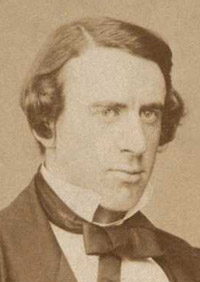

Charles Baxter

“I was often at Swanston, and it seems but yesterday that at the west end of Princes St, Louis stood by me tracing with his stick on the pavement the plan of the roads by which I was to come on my first visit. I had known him long before, but then began our friendship. It was that night, late, in his bedroom, after reading to me (I think) “The Devil on Cramond Sands”, he flung himself back on his bed in a kind of agony exclaiming, ‘Good God, will anyone ever publish me!’ To soothe him, I (quite insincerely) assured him that of course someone would, for I had seen worse stuff in print myself”(Charles Baxter in a letter to Lord Guthrie 25 March 1914. From The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol i [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 41.)

Charles Baxter (1848-1919) was a lawyer and one of RLS’s closest friends. They met in 1871 and developed a lifelong friendship. The two would often visit Swanston (see quotation above). Baxter, like RLS, had gone to Edinburgh University and both were members of the Speculative Society. Baxter was also part of RLS’s circle of friends in his student days of the 1870s, along with Bob Stevenson, Walter Ferrier and Walter Simpson. The young men would often drink in pubs on the Lothian Road, Edinburgh. He was a member of the LJR (Liberty, Justice, Reverence) League, the club RLS and his friends founded in a pub in Advocate’s Close, Edinburgh.

In 1871, Baxter became a Writer to the Signet and later joined his father’s law firm. Eventually, Baxter became RLS’s solicitor, dealing with his personal and financial business. After 1892, he also dealt with RLS’s publishers. With Sidney Colvin, he came up with the idea for the Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Robert Louis Stevenson.

Baxter married Grace Roberta Louisa Stewart in 1877, with RLS as his best man. He and his wife had two sons and a daughter. In the 1890s, Baxter went through a difficult period: he had financial problems, his wife died in 1893, and his father died the following year. Baxter had a breakdown and turned to drink. He had planned to visit RLS in Samoa, but while he was en route, he learned that Stevenson had died. Baxter was the executor for Stevenson’s estate.

In 1895, Baxter remarried. He and his wife Marie Louise Gaukroger had a daughter. Now retired, Baxter and his family lived in Paris and Sienna, Italy, returning to England during the first World War.

Baxter was a supportive friend to RLS during trying times in the author’s life. For example, in the quarrel with W.E. Henley, Baxter kept up his friendship with Henley while also helping RLS and Fanny through this difficult period.

RLS used Baxter as the inspiration for his character Michael Finsbury in The Wrong Box (1889). He wrote:

“Michael was something of a public character. Launched upon the law at a very early age, and quite without protectors, he has become a trafficker in shady affairs. He was known to be the man for a lost cause; it was known he could extract testimony from a stone, and interest from a gold mine [. . . ]. In private life, Michael was a man of pleasure; but it was thought his dire experience at the office had gone far to sober him, and it was known that (in the matter of investments) he preferred the solid to the brilliant” (RLS, with Lloyd Osbourne, The Wrong Box [London: Longmans, Green and Co, 1889], p. 16).

Stevenson also dedicated both Kidnapped (1883) and Catriona (1893) to Baxter. The dedications suggest that RLS was often thinking nostalgically about the time that he spent with Baxter in Edinburgh (a place which, at the time of writing these novels he would never live in again). In the Kidnapped dedication he wrote:

“I think I see you, moving there by plain daylight, beholding with your natural eyes those places that have now become for your companion a part of the scenery of dreams. How, in the intervals of present business, the past must echo in your memory! Let it not echo often without some kind thought of your friend” (RLS, Kidnapped [New York: Harper Brothers, 1921], p. x).

Sidney Colvin

“If you want to realize the kind of effect he made, at least in the early years when I knew him best, imagine this attenuated but extraordinarily vivid and vital presence, with something about it that at first struck you as freakish, rare, fantastic, a touch of the elfin and unearthly, a sprite, an Ariel”

(Sidney Colvin, Memories and Notes of Persons and Places, 1852-1912 [London: E. Arnold, 1921], p. 101)

Sidney Colvin (1845-1927) was a critic, scholar and one of RLS’s closest friends. Colvin and RLS first met in July 1873, when RLS was visiting his cousin at Cockfield Rectory in Suffolk. On 26 July 1873, RLS had met Fanny Sitwell at Cockfield, and had immediately fallen in love with her. Estranged from her husband, she and Colvin were in a relationship, a fact unknown to Stevenson. Fanny felt that Stevenson should meet Colvin, who could help to support his literary ambition. From their meeting at Cockfield, Colvin, Sitwell and RLS developed a lifelong friendship.

After studying at Cambridge University, Colvin settled in London. He became a fine arts critic, writing for the Pall Mall Gazette, the Fortnightly Review and the Portfolio, among others. He was elected Slade Professor of Fine Arts at Cambridge in 1873, and subsequently re-elected four more times. He was also the Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum. In 1884, Colvin became the Keeper of the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum. As part of his new role, Colvin moved into apartments in the museum. RLS would often stay with him there.

Colvin was knighted in 1911. He also wrote a biography on Keats, John Keats. His Life and Poetry, His Friends, Critics and After-Fame (1917). In addition, he published an autobiographical work, Memories and Notes of Persons and Places, 1852-1912 (1921). In one of the chapters he described his friendship with RLS. He wrote about RLS again in Robert Louis Stevenson: His Work and Personality (1924).

Colvin had met and fallen in love with Fanny Sitwell in the 1860s, who was married. The couple were unable to marry until July 1903. Their friendship with Stevenson was not always easy. Colvin disliked RLS’s wife and deeply disapproved of Stevenson’s decision to settle in Samoa (overlooking the fact that RLS’s health would not permit him to make the exhausting journey back to the UK). He believed that the decision was disrespectful to their friendship, and that Stevenson’s literary career would suffer – Colvin particularly disliked RLS’s writing from Samoa.

Even after Stevenson’s death, Colvin struggled with Stevenson – but this time with his literary legacy. He had hoped to write Stevenson’s biography, but arguments with Fanny Stevenson and Lloyd about what could and would be written caused him to drop the project. Graham Balfour took it up instead, publishing The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson (1901). Colvin had also worked on the publication of RLS’s letters (1899), but was having difficulties with Lloyd over payment. Despite these problems, Colvin worked on the Edinburgh Edition of The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson (with Charles Baxter).

Stevenson wrote a poem, for Colvin, “To S.C.” from the South Seas in 1889. The poem suggests that RLS was thinking nostalgically about the past and of his friends in the UK:

To S.C.

I HEARD the pulse of the besieging sea

Throb far away all night. I heard the wind

Fly crying and convulse tumultuous palms.

I rose and strolled. The isle was all bright sand,

And flailing fans and shadows of the palm;

The heaven all moon and wind and the blind vault;

The keenest planet slain, for Venus slept.

The king, my neighbour, with his host of wives,

Slept in the precinct of the palisade;

Where single, in the wind, under the moon,

Among the slumbering cabins, blazed a fire,

Sole street-lamp and the only sentinel.

To other lands and nights my fancy turned –

To London first, and chiefly to your house,

The many-pillared and the well-beloved.

There yearning fancy lighted; there again

In the upper room I lay, and heard far off

The unsleeping city murmur like a shell;

The muffled tramp of the Museum guard

Once more went by me; I beheld again

Lamps vainly brighten the dispeopled street;

Again I longed for the returning morn,

The awaking traffic, the bestirring birds,

The consentaneous trill of tiny song

That weaves round monumental cornices

A passing charm of beauty. Most of all,

For your light foot I wearied, and your knock

That was the glad reveille of my day.

Lo, now, when to your task in the great house

At morning through the portico you pass,

One moment glance, where by the pillared wall

Far-voyaging island gods, begrimed with smoke,

Sit now unworshipped, the rude monument

Of faiths forgot and races undivined:

Sit now disconsolate, remembering well

The priest, the victim, and the songful crowd,

The blaze of the blue noon, and that huge voice,

Incessant, of the breakers on the shore.

As far as these from their ancestral shrine,

So far, so foreign, your divided friends

Wander, estranged in body, not in mind.

Apemama.

(RLS, “To S.C.”, Songs of Travel, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol xiv [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911], pp. 244-45).

James Walter Ferrier

“Ferrier was consumed and wrecked by a miserable craving for drink. Will he, I have still to ask myself as I write these words, will he outlive the tendency, and become a conscientious, and kind gentleman as we knew him in his sober hours? Or will he go downward to the sot, the spunge and the buffoon? When last I parted from him, five months ago, he and I, for the first time in our intimacy, shed tears together over this alternative; he promised me, for my sake as well as for his own, to continue the good fight; and yet ever since I feared to write him”

(RLS in a “fragmentary autobiography” written c. 1880, from The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol iii [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 64)

James Walter Ferrier (1850-1883) was one of RLS’s friends from his days at Edinburgh University. Ferrier (along with RLS) was one of the co-editors of the College Magazine at the university. Although the magazine was a failure, RLS enjoyed working on it. He wrote about his memories of editing with Ferrier in “A College Magazine” in Memories and Portraits (1887).

Ferrier, Charles Baxter, Walter Simpson and Bob Stevenson made up RLS’s circle of friends in the 1870s – the young men would frequent the bars and brothels together in Edinburgh.

Tragically, Ferrier died of alcoholism as a young man. Stevenson was deeply grieved to lose someone who he felt such affection for. He wrote a tribute to Ferrier in the essay “Old Mortality” (1884): “Well, now he is out of the fight: the burden that he bore thrown down before the great deliverer” (“Old Mortality”, in Memories and Portraits, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol ix [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911], p. 34).

Sir Edmund William Gosse

“I have a ludicrous memory of going, in 1878, to buy him a new hat, in company with Mr Lang, the thing then upon his head having lost the semblance of a human article of dress. Aided by a very civil shopman, we suggested several hats and caps, and Louis at first seemed interested; but having presently hit upon one which appeared to us pleasing and decorous, we turned for a moment to inquire the price. We turned back, and found that Louis had fled, the idea of parting with the shapeless object having proved to painful to be entertained”

(Edmund William Gosse, Critical Kit-Kats [London: W. Heinemann, 1896], p. 282)

Edmund William Gosse (1849-1928) was a critic, author, poet and close friend to RLS. RLS first met Gosse in August 1870 on board a ship bound for Erraid (J.R. Hammond, A Robert Louis Stevenson Chronology [Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 1997], p. 7).

At that time, RLS was still getting his “education of an engineer”, and he spent three weeks on Erraid during the construction of the Dhu Heartach lighthouse (constructed between 1867-1872).

The two men did not become close, however, until 1877 (according to Graham Balfour, The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson [London: Elibron, 2005], p. 105). The men lunched at the Savile Club in London and a lifelong friendship was born. RLS and Gosse exchanged many letters and Gosse visited the Stevensons at Braemar while RLS was writing Treasure Island (1883).

Gosse was an art critic (particularly interested in sculpture), an English Literature lecturer at Cambridge University and chief librarian of the House of Lords Library. He published many volumes of poetry, and introduced readers in the UK to Henrik Ibsen’s work. He is probably most famous for his autobiographical work, Father and Son (1907). He was knighted in 1925.

Gosse also wrote literary criticism – in his Critical Kit-Kats (1896) he described RLS: “At the tail of this chatty, jesting little crowd of invaders came a youth of about my own age, whose appearance, for some mysterious reason, instantly attracted me. [Stevenson] was tall, preternaturally lean, with longish hair, and as restless and questing as a spaniel” (Edmund William Gosse, Critical Kit-Kats, [London: Heinemann, 1896], p. 276).

William Archer. literary frind of RLS, was also a friend of Gosse and a fellow-Ibsenite; W. E. Henley, however, seems to have disltrusted him and usually referred to him in letters to RLS as ‘Becky’ or ‘Becky Sharp’.

Stevenson wrote about Gosse in “Talk and Talkers: I” (1882), referring to his friend as “Purcel”: “He is no debater, but appears in conversation, as occasion rises, in two distinct characters, one of whom I admire and fear, and the other love” (“Talk and Talkers: I”, in Memories and Portraits, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol xi [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911], p. 92).

William Ernest Henley

Apparition

Thin-legged, thin-chested, slight unspeakably,

Neat-footed and weak-fingered: in his face

Lean, large-boned, curved of beak, and touched with race,

Bold-lipped, rich-tinted, mutable as the sea,

The brown eyes radiant with vivacity

There shines a brilliant and romantic grace,

A spirit intense and rare, with trace on trace

Of passion and impudence and energy.

Valiant in velvet, light in ragged luck,

Most vain, most generous, sternly critical,

Buffoon and poet, lover and sensualist:

A deal of Ariel, just a streak of Puck,

Much Antony, of Hamlet most of all,

And something of the Shorter-Catechist.

(W.E. Henley, “Apparition”, in Poems [London: David Nutt, 1889], p. 39).

“For me there were two Stevensons: the Stevenson who went to America in ’87; and the Stevenson who never came back. The first I knew and loved; the other I lost touch with, and, though I admired him, did not greatly esteem”

(W.E. Henley,”RLS”, Pall Mall Gazette, xxv [December 1901], pp. 505-14).

W.E. Henley (1849-1903) was a poet, playwright, journalist, critic, editor and friend (though the relationship was turbulent) to RLS. From a young age he suffered from tuberculosis of the bone. The disease caused him great pain, and in 1868 his left leg was amputated. He was fitted with a wooden leg (Stevenson based his pirate with a wooden leg, Long John Silver in Treasure Island [1883], on Henley). When in 1873 his right leg began to be affected by the disease, he sought treatment at the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh.

Joseph Lister, a pioneer in sterile surgery, treated Henley. He was able to save Henley’s right leg, but Henley had to spend almost two years in the hospital. It was here, on 12 February 1875, that RLS and Henley first met. Leslie Stephen, the editor of the Cornhill Magazine introduced them. Henley wrote about his time convalescing in In Hospital (1873-1875 – one of these poems was his description of RLS, “Apparition”, above).

Henley often struggled to make a living. In 1875 he worked for the Encyclopedia Britannica in Edinburgh. In London, he contributed to journals like the Atheneum, the Saturday Review and the Pall Mall Gazette. He was an editor for the London magazine. Later, he was editor for the Magazine of Art. He had some success with his poetry, in particular A Book of Verses (1888).

In 1889 he edited The Scots Observer (which later became The National Observer). He unfortunately lost the position, but in 1894 he became editor for The New Review. Here (as well as in the Observer) Henley introduced the public to authors like Joseph Conrad, Rudyard Kipling, H.G. Wells and W.B. Yeats.

Henley married Anna Boyle on 22 January 1878. The couple had only one child (after many miscarriages), Margaret Emma. She was born on 4 September 1888. She was also the inspiration for J.M. Barrie’s Wendy in Peter Pan (1904). Tragically, she died on 11 February 1894 – she was only five years old.

As young men, RLS and Henley were excellent friends. Henley helped RLS with his literary ambitions: he secured the deals for the publication of Treasure Island with Cassell and A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885) with Longmans.

By the late 1880s, however, their friendship had grown strained. The quotations above, give an indication of the change in Henley’s feelings for RLS. In the poem he refers to RLS as a young man, filled with “brilliant and romantic grace”. In the second quotation (written after RLS’s death), however, Henley talks about Stevenson as if he were his own double-natured creation in Jekyll and Hyde(1886). For Henley, the real Stevenson never re-emerged after he left for America in 1887.

The reasons for this change in the friendship were many. Henley disliked RLS’s wife, and felt that she interfered with their friendship. Furthermore, Henley was more convinced about the viability of the plays that the writers had been collaborating on than RLS. In 1879, he and RLS had written Deacon Brodie. In 1884, they wrote Beau Austin, and Admiral Guinea and in 1885 they wrote Macaire. Henley, who was often worried about money, thought the plays would be lucrative. RLS, however, was less excited about continuing the collaboration. He also felt that the plays were not a literary success. Henley was hurt, and then men quarreled.

Their biggest quarrel came in March 1888. Henley accused Fanny of plagiarism when she published the short story “The Nixie” in Scribner’s Magazine (March 1888). He argued that “The Nixie” had actually been taken from one of Katharine De Mattos’s own stories. Henley wrote to RLS on 9 March 1888:

“I read ‘The Nixie’ with considerable amazement. It’s Katharine’s; surely its Katharine’s? The situation, the environment, the principal figure – voyons! There are even reminiscences of phrase and imagery, parallel incident – que sais-je? It is all better focused, no doubt; but I think it has lost as much (at least) as it has gained; and why there wasn’t a double signature is what I’ve not been able to understand” (The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol vi [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 130).

Stevenson replied on around 22 March 1888: “I write with indescribable difficulty; and if not with perfect temper, you are to remember how very rarely a husband is expected to receive such accusations against his wife” (The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol vi [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 131).

Even after all of their difficulties, RLS still missed his friend. His description of Henley, before their greatest argument, gives an indication of what Henley was like: “Burly [Henley] is a man of great presence; he commands a larger atmosphere, gives the impression of a grosser mass of character than most men. It has been said of him that his presence could be felt in a room you entered blindfold [. . . ] There is something boisterous and piratic in Burly’s manner of talk” (“Talk and Talkers: I”, in Memories and Portraits, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol xi [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911], p. 88).

Still, even after RLS’s death, Henley could not resist one final attack on RLS and Fanny in the Pall Mall Gazette in 1901 (some of which is quoted above). He was probably angry because of Graham Balfour’s The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson (1901) – in it, Balfour published a letter from RLS to Charles Baxter in which RLS insulted Henley. RLS had been sending money to Henley, and the letter referenced this, both condescendingly and hurtfully.

Indeed, Henley and RLS never fully recovered their friendship. Towards the end of RLS’s life, though, they exchanged friendlier letters (although there was another falling out in 1890 – RLS learned that Henley had not visited RLS’s mother in Edinburgh when he was living there). The Stevensons wrote Henley a sympathy letter when his daughter died.

It seems that while in England Fanny and Katharine had discussed the story. Fanny suggested that instead of it being about an escapee from a lunatic asylum, that it should be about a water sprite – a nixie. Fanny understood that if Katharine could not publish her version, Fanny would publish her own. Afterwards, Katharine said that she had not expected Fanny to go ahead with the publication, and was hurt by what had happened. Bob Stevenson took his sister’s and Henley’s view of the event, while RLS took Fanny’s side. The quarrel damaged his relationship not only with Henley, but also with both of his cousins.

Fleeming Jenkin

“As everybody knows, Louis Stevenson was only intermittently in Edinburgh during the years that followed; its ‘icy winds and conventions’ always drove him away. He never looked really well or happy there, and I believe he owed some of his lightest-hearted hours to the friendship of Professor and Mrs Jenkin. One can scarcely imagine what he would have done or been without them. Certainly it is impossible to recall the Louis Stevenson of the seventies except as one ‘a favoured one of’ that delightful Jenkin coterie”

(Flora Masson, “Louis Stevenson in Edinburgh”, in I Can Remember Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Rosaline Masson [Edinburgh: W. & R. Chambers, 1922], 127)

Henry Charles Fleeming [pronounced ‘Flemming’] Jenkin (1833-1885) was Professor of Engineering at Edinburgh University. He is perhaps best knows for his invention of telpherage (a system of using electricity to transport vehicles or goods).

Jenkin worked (among other things) as a railroad engineer and later a cable engineer, helping to lay cables for the telegraph system in the Mediterranean.

Jenkin had many interests, including art, languages and drama. Indeed, RLS was not only one of Jenkin’s students, he also participated in the amateur theatricals that frequently took place in the Jenkin household. Fleeming and his wife Annie Austin Jenkin welcomed Stevenson into their home, and RLS had fond memories of the time he spent with them.

Further Reading:

Colin Hempstead and Gillian Cookson, A Victorian Scientist and Engineer: Fleeming Jenkin and the Birth of Electrical Engineering (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000)

For more about Stevenson on Jenkin, see Memoir of Fleeming Jenkin (1887) – an account of Jenkin’s life from his ancestors to the present, but also of RLS’s personal memories of the professor.

RLS wrote about Jenkin in “Talk and Talkers: I”, referring to him as Cockshot: “[Cockshot] has been meat and drink to me for many a long evening. His manner is dry, brisk, and pertinacious, and the choice of words not much. The point about him is his extraordinary readiness and spirit” (“Talk and Talkers: I”, in Memories and Portraits, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol xi [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911], p. 89).

Andrew Lang

“On reading ‘Ordered South’, I saw, at once, that here was a new writer, a writer indeed; one who could do what none of us, nous autres, could rival, or approach. I was instantly ‘sealed of the Tribe of Louis’, an admirer, a devotee, a fanatic, if you please. . . ”

(Andrew Lang, Adventures Among Books [London: Longmans, Green and Co, 1905], p. 44)

Andrew Lang (1844-1912) was a poet, literary critic, journalist, historian and friend to RLS. The men met on 12 February 1874 in Menton. Stevenson had been “ordered south” to Menton for health reasons in 1873. Lang was also there to convalesce.

RLS wrote: ‘Yesterday, we had a visit from one of whom I had often heard from Mrs. Sellar – Andrew Lang. He is good-looking, delicate, boyish, Oxfordish, etc. He did not impress me unfavourably; nor deeply in any way’

(Letter from RLS to his mother, 13 February 1874, The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol I [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 483).

Although RLS claimed not to be very interested, he and Lang remained friends for the rest of RLS’s life. Lang also wrote an introductory essay for the Swanston edition (1911) of The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson:

Lang is probably best known for his writings on folklore, mythology and religion. In particular he is remembered for his important work in collecting together traditional English fairy tales and folk stories in Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books. These twelve volumes were published from 1889 – 1910. Lang was also an extremely versatile and prolific writer, producing works on anthropology, psychical research, the Classics, and history.

“So much has been written on R. L. Stevenson, as a boy, a man, and a man of letters, so much has been written both by himself and others, that I can hope to add nothing essential to the world’s knowledge of his character and appreciation of his genius. What is essential has been said, once for all, by Sir Sidney Colvin in “Notes and Introductions” to R. L. S.’s Letters to His Family and Friends. I can but contribute the personal views of one who knew, loved, and esteemed his junior that is already a classic; but who never was of the inner circle of his intimates. We shared, however, a common appreciation of his genius, for he was not so dull as to suppose, or so absurd as to pretend to suppose, that much of his work was not excellent”

(Lang, “Introductory Essay”, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, vol I [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911]).

Will H. Low

“Industrious idleness it was to him; for his mind was a treasure-house, where every addition to its store was carefully guarded against the day of need. Many incidents of our common experience, long forgotten by me, I have thus met in fresh guise in after years”

(Will Low, A Chronicle of Friendships, 1873-1900 [New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908], p. 151).

Will Hicok Low (1853-1932) was an American painter and friend to RLS. RLS met Low in 1875 in France, where Low was studying art. From the mid to late 1870s, RLS, Low and Bob Stevenson would often spend time together in Paris, and the artist communities around Fontainebleau like Grez and Barbizon.

RLS wrote about this bohemian French lifestyle in The Wrecker (1892). He dedicated the ‘Epilogue’ of the novel to Low: ‘For sure, if any person can here appreciate and read between the lines, it must be you – and one other, our friend. All the dominos will be transparent to your better knowledge; the statuary contract will be to you a piece of ancient history; and you will not have now heard for the first time of the dangers of Rousillon. Dead leaves from the Bras Beau, echoes from Lavenue’s and the Rue Racine, memories of a common past, let these be your bookmarkers as you read. And if you care for naught else in the story, be a little pleased to breathe once more for a moment the airs of our youth” (RLS, with Lloyd Osbourne, The Wrecker [London: Cassell and Co., 1892], p. 427).

As the “Epilogue” suggests, Low and RLS remained friends long after their youthful days in the artist communities of France were over. Indeed, Stevenson and Fanny visited Low and his wife in Paris in August 1886. Low was also among the people who came to greet RLS when he arrived in New York on 7 September 1887.

Low published his memoirs in A Chronicle of Friendships, 1873-1908 in 1908. Here, he remembers the time he spent with RLS, particularly their experiences in France.

From 1882-1885, Low taught at Cooper Union college in New York. Later, he taught at the school of the National Academy of Design. He also illustrated Hamilton Wright Mabie’s In Arcady (1909). Low was also an art critic, writing for Scribner’s and The Century.

Low was born in Albany, New York. As a young man he studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. After his studies he returned to New York and in 1878 he joined the Society of American Artists. In 1890 he became a member of the National Academy of Design. Low designed panels for the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City and stained glass windows for both private buyers and churches like St Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Newark, New Jersey.

Wyatt Eaton

“It was in the mazes of a contra-dance at Barbizon, in the picturesque setting of a barn lighted by candles, that their first meeting took place, where Mr. Eaton, though still a student in the schools of Paris, had taken a studio to be near Jean François Millet, and hither Stevenson had come, with his cousin, known as ‘Talking Bob,’ to take part in the harvest festivities among the peasants.”

(Charlotte Eaton, A Last Memory of Robert Louis Stevenson [New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1916], p. 7)

Canadian-born Wyatt Eaton (1849-96) belonged to a constellation of painters and sculptors that also included Stevenson: the latter’s friendship with Low and Eaton flourished in the French artists’ colonies of Grez-sur-Loing and Barbizon in the neighbourhood of the Forest of Fontainebleau.

The friendship continued when RLS was in the USA in 1888. There, the circle of friends also included other noted artists of the day: the Irish-born American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens (who made the preliminary sketches for his bas-relief medallion of RLS at New York City and Manasquan/Brielle), and the older Frederic Edwin Church (a leading figure of the Hudson River School of American landscape painters) whose large-scale painting “Heart of the Andes” (1859) had been acclaimed on both sides of the Atlantic. And, of course, these artist friends, whose wives were often trained artists, were part of inter-connected circles of American artists and patrons. For example, Eaton was also a friend of painter and stained-glass artist John La Farge (who frequently met Stevenson during his stay in Samoa with Harvard historian Henry Adams from October 1890 to the end of January 1891).

This page has been contributed by Bridget Falconer-Salkeld

For full illustrated accounts of Stevenson’s sojourn at Manasquan/Brielle, see Bridget Falconer-Salkeld, “Manasquan Visited” and “Manasquan Re-Visited”, in The Robert Louis Stevenson 150th Birthday Anniversary Book, ed. Karen Steele (Edinburgh: privately printed for the RLS Club, 2000) pp. 41–49. Charlotte Eaton published her first-hand memories in several places: A Last Memory of Robert Louis Stevenson (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1916; reprinted Folcroft, Pa.: Folcroft Library Editions, 1977); Stevenson at Manasquan(Chicago: The Bookfellows, 1921); “R.L.S. at Manasquan,” Queen’s Quarterly, 38 (1931): 678–90. See also Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Wyatt Eaton.

Wyatt Eaton (1849–96) is known to readers of Stevenson for his pen-and-ink sketch of RLS, which first appeared in the Philadelphia Press, 24 March 1888.

Wyatt Eaton and Charlotte, his wife, were residing nearby at a summer artists’ colony on the estate of the New York artist Nestor Sanborn and his wife Carolyn Cook Sanborn, artist and a friend of Walt Whitman. This was situated at Point Pleasant, on the opposite bank of the Manasquan, a mile wide at that point and crossed by a wooden footbridge. Eaton, Low, and Stevenson, almost exact contemporaries, artists in several genres, basked in each other’s company during those four weeks on the Jersey shore before RLS embarked at San Francisco for the South Pacific.

After his sojourn at Saranac Lake, Upper New York State, RLS and his party returned to New York City where Will Low, his friend William B. Faxon (1849–1941) a New York artist, and Saint-Gaudens, were among the visitors Stevenson received at his hotel. On 2 May 1888 the heat of the city was exchanged for the cooling breezes and quality of light at the New Jersey shore — a destination equivalent to the coasts of Normandy and Brittany for French and European artists. Will Low, who with his wife had a summer cottage at Brielle on the Manasquan River, arranged for the Stevenson party to stay there at the waterside Union House (described by RLS in a letter to Sidney Colvin of 7 May 1888 as “a delightful country inn, like a country French place”).

In 1877 Wyatt Eaton was among the four founding members of the American Art Association (from 1878, the Society of American Artists), the others being Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Walter Shirlaw, and Helena de Kay Gilder. The following year Will Low became the fifteenth elected member.

In October 1872 Wyatt Eaton had enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts, Paris, in the atelier Gérôme where Will Low was also a student, and it was through their mutual friend, R. A. M. Stevenson, cousin of RLS and also a student at the École, that their friendship with RLS began and was further fostered by their out-of-term residencies at the artist colonies of Fontainebleau. Eaton and Will Low were particularly close friends, Eaton being a witness to Low’s marriage in 1878 (McKinney Library, Albany Institute of History and Art, New York. BR418, Box 1, F-15).

Auguste Rodin

“How I wish I could have my child’s soul and fairy religion of yore to uphold me! My dear friend, I envy you if you have still your pen at the service of your thoughts. . . I congratulate you (on your book). We have the misfortunes that come with age; but you have compensations; and the respect shown to you by your younger contemporaries who accept your advice is no common thing. Good-bye, my dear great friend Affectionately yours, RODIN.

P.S. – And our friend Stevenson who was so dear, also lost on the way, leaving only his glorious name!”

(Auguste Rodin in a letter to W.E. Henley, 4 November 1898, from The Life and Works of Auguste Rodin by Frederick Lawton [London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1906], p. 207).

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) was a French sculptor and friend to RLS. RLS first met Rodin when he and Fanny were visiting Will H. Low in Paris in August 1886. W.E. Henley, who was also in Paris at the time, introduced them. The two became friends, exchanging letters in French.

Rodin is perhaps one of the world’s best-known sculptors. He is famous for pieces like “The Thinker”, “The Kiss” and “The Three Shades”. During his own time, his work often caused controversy, departing from the accepted modes of art of the late Victorian period. He is now considered to be one of the founders of modern sculpture.

In December 1886, RLS wrote to Rodin to tell him that his sculpture, “Le Printemps” had arrived at Skerryvore. Unfortunately it arrived with a broken arm and had to be repaired. It was later inscribed with the words “A R.L. Stevenson, au sympathique artiste, fidele ami, et cher poete, Rodin”.

Rodin admired Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883) and “The Suicide Club” (1878) and Stevenson believed in Rodin’s sculpting genius. RLS also wrote a letter defending this genius to The Times on 6 September 1886. Edward Armitage (1817-1896) had written to say that a sculpture of Rodin’s had been rejected from the Royal Academy because it was a bad piece of art. Stevenson replied:

“The public are weary of statues that say nothing. Well, here is a man coming forward whose statues live and speak, and speak things worth uttering. Give him time, spare him nicknames and the cant of cliques, and I venture to predict this man will take a place in the public heart” (The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol v [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 312).

Sir Percy Florence Shelley and Lady Jane Shelley

“There is that singular story, told by a friend of the family, Miss Blantyre Simpson, of how the late Sir Percy and Lady Shelley both believed that Shelley had been re-born in Robert Louis Stevenson, and how Lady Shelley went so far as to bear a deep resentment against Mrs Stevenson as the mother of the child that ought to have been her own!”

(William Sharp, Literary Geography [London: Offices of the Pall Mall Publications, 1904], p. 33)

Sir Percy Florence Shelley (1819-1889) and Lady Shelley (Jane St John, nee Gibson, 1820-1899) befriended RLS and Fanny when they were living in Bournemouth. Sir Percy was the son of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) and novelist Mary Shelley (1797-1851). In 1844, Sir Shelley became the 3rd Baronet of Castle Goring, Sussex. He enjoyed hobbies like amateur photography and he took photographs of RLS and Skerryvore.

In July 1885, Fanny Stevenson wrote about the Shelleys to Sidney Colvin: ‘Also we are rather intimate with the Shelleys. Lady Shelley is delicious; naturally no longer young, suffering from the effects of a terrible accident that has left her a hopeless invalid, but with all the fire of youth, and as mad as some other people you know, and ready to plunge into any wild extravagance at a moment’s notice. Sir Percy is an odd creature! Do you know him? He is the poet’s son only in being so exceedingly curious. I think we will come to be very fond of him. They have a lovely little theatre at their place here, and give very delightful entertainments, which will be pleasant for us. They have a bust of Mary Wollstonecraft done from a death mask, over which Louis raves; and justly, for it is the most entrancing thing ever seen’ (The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol v [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], pp. 120-21).

RLS dedicated The Master of Ballantrae (1889) to the couple: “It is my hope that these surroundings of its manufacture may to some degree find favour for my story with seafarers and sea-lovers like yourselves. And at least here is the dedication from a great way off: written by the loud shores of a subtropical island near upon ten thousand miles from Boscombe Chine and Manor: scenes which rise before me as I write, along with the faces and voices of my friends. Well, I am for the sea once more; no doubt Sir Percy also” (RLS, “Dedication”, Waikiki, 17 May 1889, The Master of Ballantrae [London: Cassell and Co., 1891], p. iii).

Sir Walter Grindlay Simpson

‘Athelred [Simpson], on the other hand, presents you with the spectacle of a sincere and somewhat slow nature thinking aloud. He is the most unready man I ever knew to shine in conversation. You may see him sometimes wrestle with a refractory jest for a minute or two together, and perhaps fail to throw it in the end. And there is something singularly engaging, often instructive, in the simplicity with which he thus exposes the process as well as the result, the works as well as the dial of the clock’

(RLS, “Talk and Talkers: I”, in Memories and Portraits, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol ix [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911] pp. 81-93, p. 90)

Walter Grindlay Simpson (1843-1898) was one of RLS’s closest friends from his student days at Edinburgh University. Simpson’s sister, Eve Blantyre Simpson, wrote about their meeting in The Robert Louis Stevenson Originals (1912):

“My father decided during this time, when facing his end, that Walter had better adopt that Bar as his profession, so it came about that the near neighbours and Academy boys, the future fellow-travellers, the ‘Cigarette’ and the ‘Arethusa’, at last met at the Speculative Society. R.L.S., speaking of this time, says: ‘I had six friends: Bob, I had by nature, then came good James Walter [Ferrier], next I found Baxter, fourth came Simpson, somewhere about the same time I began to get intimate with Jenkin, and last came Colvin’” (E. Blantyre Simpson, The Robert Louis Stevenson Originals [London: T.N.Foulis, 1912] p. 70).

Simpson was Captain of the Honourable Company of Golfers in 1886 and 1887. Indeed, his love for the sport led him to publish frequently on the topic. His The Art of Golf (1887) is still a popular golfing book – a new edition of the work was brought out in 2008 (The Art of Golf [Cambridge: Oleander Press, 2008]).

Walter Simpson was the son of Sir James Young Simpson (1811-1870), a pioneer in the history of medicine. He introduced chloroform for medical use. He was made a baronet in 1866, and Walter succeeded to the baronetcy in 1870. Walter studied at Caius College, Cambridge University and in 1873 he became a member of the Scottish Bar.

Simpson had a long-term relationship with Anne (Etta) Fitzgerald Mackay from 1874 and they were formally married in 1881 to the opposition of his sister and brother. In a Letter of 1888, RLS says “Two of [my old friends] have married wives who love me not” and the editor supposes that this refers to Bob and Simpson (The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol 6 [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 135 and n).

Although Simpson and he spent much of their student days carousing in the pubs in Edinburgh, Simpson should not be dismissed as simply someone RLS turned to for a good night on the town. Aside from their “inland voyage”, RLS and Simpson were regular travel companions. They took canoe trips along the Firth of Forth, travelled to Germany in 1872, cruised the Inner Hebrides on the Heron in 1874, visited Barbizon in 1875, took a walking tour of the valley of the Loing shortly after and visited Grez in 1876.

Walter Simpson was RLS’s travel companion, the “Cigarette”, in An Inland Voyage (1878) and also “Athelred” in “Talk and Talkers: I” (1882).

Fanny Sitwell

“My wife [Fanny] reminds me of an incident in point, from the youthful time when he used to make her the chief confidante to his troubles and touchstone of his tastes. One day he came to her with an early [. . .] volume of poems by Mr Robert Bridges, the present poet-laureate, in his hand; declared here was the most wonderful new genius, and enthusiastically read out to her some of the contents in evidence; till becoming aware that they were being coolly received, he leapt up crying, ‘My God! I believe you don’t like them’ – and flung the book across the room and himself out of the house in a paroxysm of disappointment – to return a few hours later and beg pardon humbly for his misbehaviour. But for some time afterwards, whenever he desired her judgement on work of his own or others, he would begin by bargaining: You won’t Bridges me this time, will you?”

(Sidney Colvin, Memories and Notes of Persons and Places, 1851-1912 [London: E. Arnold, 1912], pp. 122-23)

RLS first met Frances (Fanny) Sitwell (1839-1924) on 26 July 1873. RLS was visiting his cousin Maud Babington at Cockfield Rectory, Suffolk when Fanny was also visiting. RLS soon fell in love with her, but she was in a relationship with Sidney Colvin. On this visit to the rectory, RLS also met Colvin and the three developed a lifelong friendship.

Fanny was born Frances Jane Fetherstonhaugh in Ireland. She made an unhappy marriage with the Reverend Albert Hurt Sitwell (1824-1894). The couple had two sons, Frederick, (who died in 1873) and Francis Albert (Bertie). Fanny later brought Bertie to Davos, Switzerland, in 1881 in the hope of curing his tuberculosis. The Stevensons were also in Davos at the time. Tragically, Bertie died on 3 April 1881. He was only eighteen years old.

While some biographers suggest that she and RLS consummated their relationships physically, others reject the idea. Fanny had asked that RLS destroy her letters to him, making a full understanding of the relationship difficult. It seems, though, that in 1874 Fanny made clear how the relationship stood – they would be friends, and nothing more. They did indeed remain friends, and RLS wrote to both Colvin and Fanny for the rest of his life.

In Fanny, RLS found a confidante, a sympathetic woman who he often idealized. He wrote her intimate letters, fluctuating between writing to her as is she were his lover and treating her as a maternal figure. He often referred to her in his letters as “Madonna”, or sometimes “Claire”. His letters demonstrate the often overblown and romantic way he wrote to her, for example:

“I want to say so many things to you, that I find it impossible to begin. I want to tell you how any little detail of your life makes absence a mere dream; but on that head, dear, you know already all that I feel. And I want to tell you what I hope to do and of what I fear to fail in the accomplishment. And again, I want to tell you all manner of small things out of my own life, all sorts of infinitesimal joys and sorrows and disappointments and happy surprises, that I desire to share with my dearest of all friends; and yet these and many other things (do you understand me?) it seems a sort of insincerity to write about between us two, as when people talk of the weather for a long while, warily avoiding something of superlative interest to both” (Letter from RLS to Fanny Sitwell, 8 September 1873, The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol i [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], pp. 290-91).

After the death of her first son in 1873, Fanny became estranged from her husband. It was then that she made RLS’s acquaintance. She and Colvin offered Stevenson their support when he was arguing with his father about his loss of religious faith. They helped him to gain much-needed time away from his parents, urging Dr Andrew Clark to send him away. The doctor agreed, and RLS was “ordered south” to Menton in 1873.

Fanny worked as a secretary at the College for Working Women. She also worked as a translator and reviewer. She had met Sidney Colvin in the late 1860s, and they had fallen in love. Fanny’s husband died in 1894, but it seems that worries about money kept Fanny and Colvin from marrying until July 1903.

Sir Leslie Stephen

“At this time [Stevenson] must not be thought of as a successful author. A very few of us were convinced of his genius; but with the exception of Mr Leslie Stephen, nobody of editorial status was sure of it”

(Edmund William Gosse, Critical Kit-Kats [London: W. Heinemann, 1896], p 281).

Leslie Stephen (1832-1904) was an author, critic and editor who helped RLS with his literary career. Stephen’s editorship (1871-1882) of the Cornhill Magazine meant that he was able to publish much of RLS’s early writings. He strongly believed in Stevenson’s abilities and encouraged the young author to pursue his literary ambitions.

In his personal life, Stephen was an avid mountaineer. He married Julia Prinsep Jackson (1846-1895) and they had four children, including the novelist Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) and the painter Vanessa Bell (1879-1961).

In his Studies of a Biographer (1902), Leslie included a chapter on Stevenson discussing his literary style: “Stevenson, by whatever means, acquired not only a delicate style, but a style of his own. If it sometimes reminds one of models, it does not suggest that he is speaking in a feigned voice. I think, indeed, that this precocious preoccupation with style suggests the excess of self-consciousness which was his most obvious weakness; a daintiness which does not allow us to forget the presence of the artist. But Stevenson did not yield to other temptations which beset the lover of exquisite form. He was no ‘aesthete’ in the sense which conveys a reproach. He did not sympathise with the doctrine that an artist should wrap up himself in luxurious hedonism and cultivate indifference to active life” (Leslie Stephen, Studies of a Biographer, vol iv [London: Duckworth, 1902], pp. 215-16).

Stephen studied at Eton College and Cambridge University. During his editorship of the Cornhill Magazine, he published works not only by RLS, but also by Thomas Hardy, W.E. Norris, James Payn and Henry James. He contributed to periodicals like the Saturday Review, Fraser, Macmillan, and The Fortnightly. He also wrote philosophical texts and literary criticism. From 1885- 1891 he was the first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography. He was knighted in 1902.