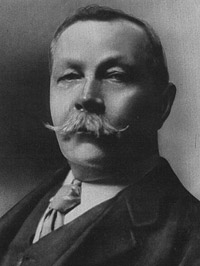

J.M Barrie

“So Mr Stevenson puzzles the critics, fascinating them until they are willing to judge him by the magnum opus he is to write by and by when the little books are finished. Over Treasure Island I let my fire die in winter without knowing that I was freezing. But the creator of Alan Breck has now published nearly twenty volumes. It is so much easier to finish the little works than to begin the great one, for which we are all taking notes. Mr Stevenson is not to be labeled novelist. He wanders the byways of literature without any fixed address”

(J.M Barrie, “Robert Louis Stevenson”, British Weekly, vol 9 [2 November 1888])

James Matthew Barrie (1860-1937) was a Scottish novelist and playwright. He studied at the University of Edinburgh before briefly becoming a journalist. His first novel was The Little Minister (1891). Although the work met with a poor critical reception, Barrie was popular with the general public, publishing works like Sentimental Tommy (1896), Margaret Ogilvy (1896) and Tommy and Grizel (1902).

Barrie was particularly interested in writing for the theatre. He wrote plays like The Admirable Crichton (1902) and What Every Woman Knows (1906).

He is best known for his character Peter Pan, the eternal youth. His play, Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up was first performed in 1904. Peter and the other boys in the story were based on the children of Arthur and Sylvia Llewelyn Davies (Barrie’s friends). The character Wendy was inspired by W.E. Henley’s daughter, Margaret Emma. Barrie wrote several works about these characters including the novels The Little White Bird: or, Adventures in Kensington Gardens (1902), Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906), When Wendy Grew Up: An Afterthought (1908) and Peter and Wendy (1911).

Barrie made an unhappy marriage to the actress Mary Ansell in 1894. The couple had no children and divorced in 1909. The author was made a baronet in 1913.

Barrie and Stevenson began their correspondence in 1892. RLS had now settled at Vailima in Samoa. In a letter from c. 18 February 1892 he outlined the reasons why he and Barrie ought to write to one another: “We are both Scots besides, and I suspect both rather Scotty Scots; my own Scotchness tends to intermittency, but is at times erisypelitous – if that be rightly spelt. Lastly, I have gathered we have both made our stages in the metropolis of the winds [Edinburgh]: our Virgil’s ‘gray metropolis’, and I count that a lasting bond. No place so brands a man” (The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol. vii [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 238).

Barrie and RLS wrote about Scottishness, their own writing (RLS particularly admired Barrie’s A Window in Thrums [1889] and The Little Minister), and other authors (RLS decried Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles [1891]). RLS also wrote Barrie a long description of himself, his family and life at Vailima in a letter in April 1893 (Letters, vol. viii, pp. 44-8) .

Barrie wrote about RLS in “Robert Louis Stevenson” for the British Weekly (1888 – above). In the article he praised RLS’s versatility, but also suggested that readers had not yet seen the best of the author.

Stevenson extended several invitations for Barrie to visit him in Samoa. After his death, Barrie wrote “Had he lived another year, I should have seen him. All plans arranged for a visit to Vailima, ‘to settle on those shores for ever’, he wrote, or something to that effect, ‘and if my wife likes you what a time you will have, and if she does not, how I shall pity you’” (J.M. Barrie, I Can Remember Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Rosaline Masson [Edinburgh: W&R Chambers, 1922], p. 292).

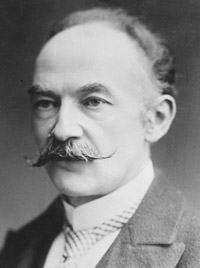

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

From RLS, 5 April 1893, to Arthur Conan Doyle:

“I hope you will allow me to offer you my compliments on your very ingenious and very interesting adventures of Sherlock Holmes. That is the class of literature that I like when I have the toothache. As a matter of fact, it was a pleurisy I was enjoying when I took the volume up; and it will interest you as a medical man to know that the cure was for the moment effectual”

Doyle responded:

“I’m so glad Sherlock Holmes helped to pass an hour for you. He’s a bastard between Joe Bell [a famous Edinburgh surgeon] and Poe’s Monsieur Dupin (much diluted). I trust that I may never write a word about him again. I had rather that you knew me by my White Company. I’m sending it on the chance that you have not seen it”.

(Correspondence between RLS and Arthur Conan Doyle, The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol viii [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], pp. 49-50)

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) was a Scottish novelist. He is best known for his Sherlock Holmes stories, such as The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892) and The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902). His fictional detective was based on Dr Joseph Bell (1837-1911) a professor at Edinburgh University (who both RLS and Conan Doyle knew).

Conan Doyle also wrote a series of science fiction stories, the Professor Challenger adventures (such as The Lost World [1912]). In addition, he wrote historic (for example The White Company [1891]) and supernatural (for example The Parasite [1894]) novels.

Conan Doyle studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh. In the early 1880s he set up a practice, but his time was soon taken up with writing his detective stories. Besides working on his fiction, Conan Doyle was also a political campaigner and an active spiritualist. The author married Louisa Hawkins in 1885 and the couple had two children. After his wife’s death, Conan Doyle married Jean Elizabeth Leckie in 1907. They had three children. Conan Doyle was knighted in 1902.

It was his famous Sherlock Holmes stories that sparked the correspondence between Conan Doyle and RLS. RLS complimented him on his detective (see the quotations beginning this section) and the authors stayed in touch, commenting on each other’s writing.

Conan Doyle went on to pose the question: “Is Stevenson a classic? Well, it is a large word that. You mean by a classic a piece of work which passes into the permanent literature of the country. As a rule you only know your classics when they are in their graves. Who guessed it of Poe, and who of Borrow? The Roman Catholics only canonize their saints a century after their death. So with our classics. The choice lies with our grandchildren. But I can hardly think that healthy boys will ever let Stevenson’s books of adventure die” (Arthur Conan Doyle, Through the Magic Door [London: Smith, Elder and Co, 1907], pp. 269-70).

Conan Doyle later wrote about Stevenson’s writing in Through the Magic Door (1907): “And Stevenson? Surely he shall have two places also, for where is a finer sense of what the short story can do? He wrote, in my judgment, two masterpieces in his life, and each of them is essentially a short story, though the one happened to be published as a volume. The one is Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, which, whether you take it as a vivid narrative or as a wonderfully deep and true allegory, is a supremely fine bit of work. The other story of my choice would be ‘The Pavilion on the Links’ – the very model of dramatic narrative. That story stamped itself so clearly on my brain when I read it in Cornhill that when I came across it again many years afterwards in volume form, I was able instantly to recognize two small modifications of the text – each very much for the worse – from the original form. (Arthur Conan Doyle, Through the Magic Door [London: Smith, Elder and Co, 1907], pp. 116-17).

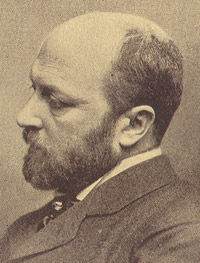

Thomas Hardy

“Well, I was mortually wounded by Tess of the Durberfields. I do not know that I am exaggerative in criticism; but I will say Tess is one of the worst, the weakest, least sane, most volulu books I have yet read [. . .] I could never finish it, there may be the treasures of the Indies further on; but so far as I read, James, it was (in one word) damnable. Not alive, not true, was my continual comment as I read, and at last – not even honest! was the verdict with which I spewed it from my mouth. I write in anger? I almost think I do; I was betrayed in a friend’s house – and I was pained to hear that other friends delighted in the barmecide feast. I cannot read a page of Hardy for many a long day, my confidence is gone. So that you and Barrie and Kipling are now my Muses Three. And with Kipling, as you know, there are reservations to be made. And you and Barrie don’t write enough”

(Letter from RLS to Henry James, 4 December 1892, The Collected Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol vii [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 450)

“Did I tell you that we saw Hardy the novelist at Dorchester? A pale, gentle, frightened little man, that one felt an instinctive tenderness for, with a wife – ugly is no word for it, who said ‘whatever shall we do?’ I had never heard a living being say it before”

(Letter from Fanny Stevenson to Margaret Stevenson, 10 September 1885, The Collected Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol v [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 125)

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) was a major writer of the Victorian period, best known now and in his time for his novels. These include Far from the Madding Crowd (1874), The Return of the Native (1878), The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), The Woodlanders (1887 – RLS wanted to take this novel with him when he left for the USA in 1887. He sent his friend Edmund Gosse to find it for him), Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) and Jude the Obscure (1895).

Hardy also wrote short stories, plays, and many volumes of poetry, including Wessex Poems and Other Verses (1898). His writing is often extraordinarily bleak, with recurring themes of loss, the struggle against circumstances and fate, and suffering.

Although he trained to be an architect, Hardy decided to pursue a writing career. He left London (where he had been living) and returned to Dorset, where he was born and spent his childhood. He married Emma Lavinia Gifford in 1874. Hardy was deeply distressed by her death in 1912 and wrote many poems about their complicated relationship. He married Florence Emily Dudgate in 1914.

RLS first met Thomas Hardy in Dorchester at the end of August or early September 1885. RLS, Fanny, Lloyd and Katherine de Mattos visited Hardy in his new home, Max Gate, Dorchester. For more information about this visit, see the passage devoted to Dorchester in the Footsteps section.

In early June 1886, RLS wrote to Thomas Hardy about the possibility of dramatizing his The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886). Hardy replied on 7 June: “I feel several inches taller at the idea of your thinking of dramatizing the Mayor, Yes, by all means” (from The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol v [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 259). Despite Hardy’s seeming enthusiasm, nothing more came of RLS’s proposal.

From around 9-12 June 1886, RLS was staying with Sidney Colvin in his apartment in the British Museum, London. On the 9th, he wrote to Thomas Hardy, asking him to dinner at Colvin’s. Hardy accepted, and they had dinner on 11 June.

Although Stevenson usually admired Hardy’s work, he strongly disliked Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), writing damning letters about the work to W.E. Henley, J.M. Barrie and Henry James (see, for example, the quotation beginning this section). William Gray argues that “the vehemence of Stevenson’s criticism of Tess may be in some measure due to its succes de scandale in an area in which he himself had had problems: the representation of sexuality in the context of Victorian publishing” (Robert Louis Stevenson: A Literary Life [Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004], p. 18).

In I Can Remember Robert Louis Stevenson (1922), Hardy contributed his own memories of the writer. He recounted the visit in Dorchester, the dinner with Colvin and the proposal for the play concluding with the words:

“I heard no more about the play; and I think I may say that to my vision he dropped into utter darkness from that date: I recall no further sight of or communication from him, though I used to hear of him in a roundabout way from friends of his and mine. I should add that some years later I read an interview with him that had been published in the newspapers, in which he stated that he disapproved of the morals of Tess of the d’Urberbvilles, which had appeared in the interim, and probably had led to his silence” (Thomas Hardy, I Can Remember Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Rosaline Masson [Edinburgh: W&R Chambers, 1922], pp. 215-16).

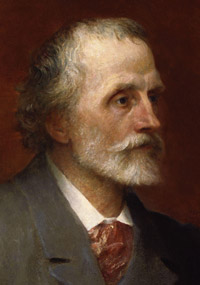

Henry James

“I meant to write to you tonight on another matter – but of what can one think, or utter or dream, save of this ghastly extinction of the beloved R.L.S? It is too miserable for cold words – it’s an absolute desolation. It makes me cold and sick – and with the absolute, almost alarmed sense, of the visible, material, quenching of an indispensable light”

(Letter from Henry James to Edmund Gosse, 17 December 1894. From Letters, ed. by Leon Edel, vol iii [Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974-84], p. 495)

Henry James (1843-1916) was an American novelist and close friend to RLS. Some of his most notable works are Daisy Miller (1878), The Portrait of a Lady (1881), The Turn of the Screw (1898), The Wings of the Dove (1902) and The Ambassadors (1903). He often wrote from the point of view of his characters, and his innovative style, using unreliable narrators and interior monologues, strongly influenced modernist writing. Although mostly known for his realist fiction, James also wrote literary criticism, plays, works on travel writing, biographical and autobiographical works.

James was born in New York City. He studied law at Harvard University , but like RLS, he wanted to be a writer and focused instead on his literary ambitions. Although an American, James felt that he identified more with Europe. Indeed, he was preoccupied with national identity. Much of his writing centers on what happens in the meeting between American and European cultures. In the end, James’s life seemed to suggest that national identity is a choice – he settled in England in 1876 and became a British citizen in 1915.

First Meeting

RLS first met Henry James in the summer of 1879. He had travelled to London on 30 July to ask his friends what they thought about his plan to go to the United States in pursuit of Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne (they tried and failed to dissuade him).

Sometime in early August, RLS, Edmund Gosse and Andrew Lang had lunch with Henry James. Although he and Stevenson later grew close, James was not terribly impressed on this first meeting. In a letter to T.S. Perry on 14 September 1879, James wrote that RLS was “a shirt-collarless Bohemian and a great deal (in an inoffensive way) of a poseur” (From Leon Edel, Henry James Letters, vol ii [Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974-84], p. 255).

On 2 July 1884, James attended the first London performance of Deacon Brodie. RLS was unfortunately too unwell to attend himself.

“The Art of Fiction” and “A Humble Remonstrance” Debate

The authors got in touch again in 1884 in a published debate about “the art of fiction”. In April 1884, Walter Besant had published a pamphlet on his lecture “The Art of Fiction”. Henry James responded in “The Art of Fiction” (Longman’s Magazine, September 1884). He was concerned with the importance of literary technique and he used Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883) as an example of how different the novel could be (while still being a novel):

“I have just been reading, at the same time, the delightful story of Treasure Island, by Mr. Robert Louis Stevenson, and the last tale from M. Edmond de Goncourt, which is entitled Chérie. One of these works treats of murders, mysteries, islands of dreadful renown, hairbreadth escapes, miraculous coincidences and buried doubloons. The other treats of a little French girl who lived in a fine house in Paris and died of wounded sensibility because no one would marry her. I call Treasure Island delightful, because it appears to me to have succeeded wonderfully in what it attempts; and I venture to bestow no epithet upon Chérie, which strikes me as having failed in what it attempts-that is, in tracing the development of the moral consciousness of a child. But one of these productions strikes me as exactly as much of a novel as the other, and as having a ‘story’ quite as much. The moral consciousness of a child is as much a part of life as the islands of the Spanish Main, and the one sort of geography seems to me to have those ‘surprises’ of which Mr. Besant speaks quite as much as the other. For myself (since it comes back in the last resort, as I say, to the preference of the individual), the picture of the child’s experience has the advantage that I can at successive steps (an immense luxury, near to the ‘sensual pleasure’ of which Mr. Besant’s critic in the Pall Mall speaks) say Yes or No, as it may be, to what the artist puts before me. I have been a child, but I have never been on a quest for a buried treasure, and it is a simple accident that with M. de Goncourt I should have for the most part to say No. With George Eliot, when she painted that country, I always said Yes.”

(Henry James, “The Art of Fiction” in The Art of Fiction by Henry James and Walter Besant [London: Cupples, Upham, 1885] pp. 79-80).

In response to James, RLS wrote “A Humble Remonstrance” (Longman’s Magazine, December 1884). RLS’s essay, with an additional paragraph, was later included in Memories and Portraits (1887). He wrote:

“[James] cannot criticize the author, as he goes, ‘because,’ says he, comparing it with another work, ‘I have been a child, but I have never been on a quest for buried treasure.’ Here is, indeed, a willful paradox; for if he has never been on a quest for buried treasure it can be demonstrated that he has never been a child. There never was a child (unless Master James) but has hunted gold, and been a pirate, and a military commander, and a bandit of the mountains; but has fought, and suffered shipwreck and prison”

(RLS, “A Humble Remonstrance”, Memories and Portraits [New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1895], p. 287).

James and RLS’s essays are both significant debates about the novel in the 1880s. After RLS’s piece was published, James wrote words “of hearty sympathy, charged with the assurance of my enjoyment of everything you write. It’s a luxury, in this immoral age, to encounter someone who does write – who is really acquainted with that lovely art” (From The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, vol v [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 42).

Stevenson replied: “I have re-read my paper, and I cannot think I have at all succeeded in being veracious or polite. I know of course, that I took your paper merely as a pin to hang my own remarks upon; but alas! what a thing is any paper! what fine remarks can you not hang on mine!” (Letter from RLS to Henry James, 8 December 1884, The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol v [New Haven: Yale University Press], p. 43).

A Lifelong Friendship

It was in 1885, that James and RLS cemented their friendship. In 1885, James was visiting his invalid sister in Bournemouth. The Stevensons had just moved into Skerryvore (early April 1885). James was one of their first visitors, and over the next couple of months he spent a great deal of time there. Both Fanny and RLS enjoyed his company. He even attended a wedding anniversary dinner they had on 19 May.

RLS met James in person for the last time on 21 August 1887 at the Armfield’s Hotel, Finsbury, London. RLS was leaving for the USA, and James (along with W.E. Henley, Coggie Ferrier, Katherine de Mattos, Aunt Margaret Scott Jones Stevenson [Aunt Alan] and Cummy) had come to say goodbye. James gave Stevenson a case of champagne as a farewell gift for the journey.

From 1885 until Stevenson’s death, RLS and James exchanged warm letters. They wrote about each other’s writing, but RLS also confided his fears about his health. Later, when in Samoa, he expressed his worry that he would never be well enough to return to the UK.

A Literary Friendship

Later, in Notes on Novelists (1914) James wrote: “The case was nevertheless that the man somehow approached them [the reader], and that to read him – certainly to read him with the full sense of his charm – came to mean for many persons much the same as to ‘meet him’. It was as if he wrote himself outright and altogether, rose straight to the surface of his prose, and still more of his happiest verse; so that these things gave out, besides whatever else, his look and motions and voice, showed his life and manners, all that there was of him, his ‘tremendous secrets’ not excepted. We grew in short to possess him entire” (Henry James, “Robert Louis Stevenson”, Notes on Novelists with Some Other Notes [New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1914], p. 1).

In turn, James praised many of RLS’s works, including Catriona (1893). He also devoted a chapter to Stevenson in Partial Portraits (1888): “Before all things he is a writer with a style – a model with a complexity of curious and picturesque garments. It is by the cut and the colour of this rich and becoming frippery – I use the term endearingly, as a painter might – that he arrests the eye and solicits the brush” (Henry James, “Robert Louis Stevenson”, Partial Portraits [London: Macmillan, 1919], pp. 139-40).

Stevenson admired James’s writing, praising Roderick Hudson (1875), The Princess Cassassmina (1886) The Tragic Muse (1890) and the short stories “The Pupil” (1891) and “The Marriages” (1892). RLS did not, however, care for Washington Square (1881). He wrote to W.E. Henley in early March 1881: “Mrs Pennyman we both adore and have always adored. And shall ever adore, world without end; which does not prevent Washington Square from being in its way, an unpleasant book, nor H. James from being a mere club fizzle [. . .] and no out-of-doors, stand-up man whatever” (The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol iii [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 159).

George Meredith

“Adieu. I trust you are well. Look to health. Run to no excess in writing or in anything. I hope you will feel that we expect much of you”

(Letter from Meredith to RLS on 4 June 1878 regarding An Inland Voyage. From Letters of George Meredith, ed. by C.L.Cline [Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970], pp. 559-61).

George Meredith (1828-1909) was an English novelist and poet. He is best known for novels like The Egoist (1879) and Diana of the Crossways (1885). He was also a reader for the publishers Chapman and Hall, reading and suggesting manuscripts for publication. In this capacity he introduced the reading public to George Gissing (1857-1903) and Thomas Hardy (1840-1928).

In 1849 Meredith made an unhappy marriage to Mary Ellen Nicolls. The couple had one child, Arthur (1853-1890). Mary Ellen left Meredith in 1858 for the artist Henry Wallis (1830-1916) and died in 1861.

In 1864, Meredith made a second, and more successful marriage. He and his new wife, Marie Vulliamy, settled in Flint Cottage, Box Hill, Dorking. They had two children, William (b. 1865) and Mariette (b. 1874). Marie died of cancer in 1885, and RLS sent the grieving Meredith a condolence letter.

RLS first met George Meredith in March 1878 at his home in Flint Cottage (Stevenson and his mother were staying in Box Hill from 15-19 March at the Burford Bridge Hotel). After this visit the authors stayed in touch, and RLS visited Meredith three more times: in early June 1879 (probably 1-8 June), from 12-17 May 1882, and from 4-8 August 1886. For more information about these visits to Box Hill, you can also see the section devoted to it in the Footsteps pages.

Both writers exchanged and expressed their admiration for one another’s work. In an April 1882 letter to W.E. Henley Stevenson wrote: “George Meredith, the only man of genius of my acquaintance [. . .]. I have just re-read for the third and fourth time The Egoist. When I shall have read it the sixth or seventh, I begin to see I shall know about it. You will be astonished when you come to re-read it; I had no idea of the matter – human, red matter, he has contrived to plug and pack into that strange and admirable book” (The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol iii [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 321).

Indeed, RLS read a great deal of Meredith, for example The Ordeal of Richard Feverel (1859), Evan Harrington (1861), The Adventures of Harry Richmond (1871), Poems and Lyrics of the Joy of Earth (1883), Diana of the Crossways (1885), and One of Our Conquerors (1891). In turn, Meredith read Stevenson’s work – for example he commented on An Inland Voyage (1878) and RLS sent him Ballads (1890) and Catriona (1893) from Samoa. RLS also dedicated the 1884 edition of Beau Austin to Meredith.

Meredith used RLS as the model for his character Gower Woodseer in The Amazing Marriage (1895). When RLS learned about Meredith’s intentions, he wrote: “I hear occasionally of The Amazing Marriage. It will be a brave day for me when I get hold of it. Gower Woodseer is now an ancient, lean, grim, exiled Scot, living and labouring for a wager in the tropics; still active, still with lots of fire in him, but the youth – ah, the youth where is it?”(Letter from RLS to George Meredith, 5 September 1893, The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Bradford A. Booth and Ernest Mehew, vol viii [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995], p. 163). Unfortunately, RLS was never to read how Meredith depicted him – he died a month before the novel began serialization in Scribner’s.