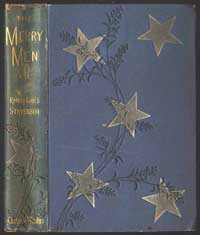

The Merry Men, 1887

The Merry Men and Other Tales and Fables Contents

“The Merry Men” (1882)

“Will o’the Mill” (1878)

“Markheim” (1885)

“Thrawn Janet” (1881)

“Olalla” (1885)

“The Treasure of Franchard” (1883)

Summaries

“The Merry Men” (1882)

In “The Merry Men” Charles pays a visit to his Uncle Gordon and cousin Mary Ellen. They live on the island of Eilean Aros, which has dangerous waters and has been the site of many shipwrecks. Indeed, the island is surrounded by treacherous reefs, known locally as “the Merry Men”. They are so named because “the noise of them seemed almost mirthful [. . .] yet instinct with a portentous joviality. Nay, and it seemed even human” (p. 107).

The Espirito Santo, a Spanish vessel laden with treasure, is said to have sunk here on Sandag Bay many years ago. When he learns that a historian is searching for the treasure, Charles vows to find it first. He hopes that the wealth he gains will enable him to marry Mary Ellen and help his uncle.

When Charles arrives, he notices that his uncle is acting strangely and seems unwell. He also notices that the house has new furniture and decorations – all of which have been salvaged from the recent wreck of the Christ-Anna on Sandag Bay.

Later, Charles sees the wreck and also notices a grave has been dug nearby. He begins to suspect his uncle of some foul play with theChrist-Anna. Nevertheless, he resolves to focus on his treasure hunt. He dives and finds a rusted belt buckle and a human leg bone. Horrified, he realizes that these must be from the the Christ-Anna.

He turns back to the beach and sees several men in a boat investigating the buckle and the bone. Their schooner is further out to sea, and Charles thinks these may be the historian and his men. A storm is brewing and the men will probably perish in the dangerous waters.

Charles and his uncle go to see what can be done for the men, but it is too late. Indeed, Uncle Gordon takes a wicked delight in watching the men’s struggles. Increasingly unhinged, he seems to think he is watching the wreck of the Christ-Anna again. Charles learns that his uncle was drunk that night, and murdered one of the survivors of the wreck – it is this man’s grave he saw earlier. Charles is relieved that at least the act was carried out in drunken madness rather than in cold blood.

Later, Charles and his uncle examine the new wreck. They see a black man, the lone survivor of the storm. Uncle Gordon thinks he is the ghost of the murdered man come to haunt him. Now insane with guilt and fear, he runs and hides on the island. Charles, the servant Rorie and the black man try to herd him to safety, but the plan backfires. Terrified of the black man, Gordon runs into the sea with the black man in pursuit – both men drown.

Quotations from “The Merry Men”, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston end, vol xxi (London: Chatto and Windus, 1911), pp. 69-124.

“Will o’ the Mill” (1878)

Will lives with his adoptive parents in a quiet and sheltered mill and wayside inn in the countryside. After seeing the sea in the distance, Will is filled with an overmastering desire to leave the mill and explore the world.

Later a traveller comes to the inn. He urges Will to be happy with his sedentary life, arguing that it is better to be a “squirrel sitting philosophically over his nuts” than “a squirrel turning in a cage” (p. 244).

Some years later Will’s parents die. Instead of leaving to see the world, Will adopts the traveler’s philosophy and is content with what he has. When the Parson and his daughter Marjory come to stay at the inn, Will soon falls in love and he and Marjory plan to marry.

One day, Marjory explains how she longs to possess the flowers in the garden when they are growing, but when she picks them they lose their allure. She reminds Will of how he once longed to look over the plains, but if he went to the plains himself he would lose the pleasure of looking. He applies this theory to marrying Marjory, believing if they wed he would lose all of the pleasure of her friendship. When he explains this to Marjory she is furious, but soon decides Will is right. They remain friends until Marjory marries someone else, and some years later she passes away.

When he is an old man, Will awakes in the middle of the night and he seems to hear the sounds and people of his past – he hears Marjory, his parents and remembers his youth. Will goes outside and finds that Death has come to the inn to take him away. Death tells Will he has long waited for someone who has never really lived at all. Will responds that he has waited for Death ever since Marjory passed away. “[W]hen the world rose next morning, sure enough Will o’ the Mill had gone at last upon his travels” (p. 263).

Quotations from “Will o’ the Mill”, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston end, vol vi (London: Chatto and Windus, 1911), pp. 235-63.

“Markheim” (1885)

Markheim enters a pawnshop and murders the shop dealer for his money. Afterwards, he is haunted both by visions of his childhood and by phantom sounds.

He is busy searching for the money when he hears steps mounting the stairs. The door opens and a face looks in at him and smiles before withdrawing. Markheim is terrified, but the “visitant return[s]” (p. 284): “the outlines of the new-comer seemed to change and waver like those of the idols in the wavering candlelight of the shop; and at times he thought he bore a likeness to himself; and always, like a lump of living terror there lay in his bosom that this thing was not of the earth and not of God” (p. 285).

The visitor offers to help Markheim find the money, advising him that the maid will shortly return to the shop and find the dealer’s body. Markheim resists, however: while he knows he has done wrong, he does not wish to collude with evil.

Markheim confronts the maid, telling her he has killed the dealer and that she should find the police. As he speaks to the maid “the features of the visitor began to undergo a wonderful and lovely change: they brightened and softened with a tender triumph, and, even as they brightened, faded and dislimned” (p. 291).

Quotations from “Markheim”, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston end, vol viii (London: Chatto and Windus, 1911), pp. 273-91.

“Thrawn Janet” (1881)

Note: The term “thrawn” is Scots for crooked, twisted or misshapen, but also means perverse or contrary. After the intoduction, this tale is narrated in Scots.

“Thrawn Janet” describes the first year of Reverend Murdoch Soulis’s ministry at Balweary in the vale of Dule.

The studious Soulis invites the old woman Janet M’Clour to act as his housekeeper at the manse. The villagers, believing she is evil, throw her into the Dule to see if she is a witch. Soulis intervenes and asks her to renounce the devil in the name of God. She does so, but the next day the villagers notice that “her neck [was] thrawn, an’ her heid on ae side, like a body that has been hangit, an a girn on her face like an unstreakit corp” (p. 309).

Soulis assures the villagers that she is suffering from a stroke of the palsy, but they believe she is not Janet at all, but rather a “bogle” or corpse possessed by the devil.

One day, Soulis sees a black man, the devil himself, who walks quickly away to the manse. Soulis cannot catch him, and when he asks Janet whether she saw him she tells him there is no such man. Soulis, however, feels uneasy and begins to suspect that Janet “was deid lang syne, an’ this was a bogle in her clay-cauld flesh” (p. 312).

One night Soulis is awoken from his sleep by strange sounds coming from Janet’s room. When he goes to investigate he sees “Janet, hangin’ frae a nail” (p. 314) – she is a corpse after all! He locks the door and runs downstairs to pray, but she follows. He beseeches the heavens and lightning strikes her down. In the morning, villagers report seeing the black man that dwelled in Janet’s body.

Ever since, Soulis is “a severe, bleak-faced old man, dreadful to his hearers” (p. 305).

Quotations from “Thrawn Janet”, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol v (London: Chatto and Windus, 1911), pp. 305-16.

“Olalla” (1885)

Set in Spain during the Peninsular War, “Olalla” is narrated by an anonymous wounded English officer. He is sent on doctor’s orders to recuperate in the mountains at the “residencia” of an old and impoverished Spanish family.

The family has a strange history: the Senora married beneath her, or possibly never married, and madness runs in the family . She has two children, Felipe and Olalla. Felipe is “an innocent” (p. 129), a mentally disabled lad, who dotes on the narrator. The Senora is strangely vacant, content with the sensuous pleasures in life.

The narrator finds the house and its occupants strange. One night he hears terrible screams but finds he is locked in his room. He is also haunted and enchanted by a painting of a beautiful woman. She is the Senora’s ancestor, and looks uncannily like both the Senora and Felipe. The painting leads him to believe that physically the family are unchanged from their predecessors – mentally, however, they seem to have degenerated.

One day he meets Olalla and is instantly attracted to her. He loves her and urges her to leave with him. She, however, fears that she will go mad as her relatives have done, and that he should leave at once.

In despair, he puts his hand through a window and his wrist bleeds copiously. He seeks help, but when the Senora sees his bleeding wrist, she leaps on it and bites to the bone. Olalla and Felipe come to his rescue.

Felipe now takes the narrator to recuperate in a nearby village. The priest tells the narrator that when the Senora was young, she was sane, but that madness had come to her later. When the narrator tells the priest Olalla fears she too will lose her sanity, the priest urges him to listen to her.

In the village a peasant tells the narrator the local superstitions and fears about the residencia, suggesting that the residents are not human. Highly skeptical, the narrator is horrified to learn the peasants plan to burn the family out of their home.

The narrator goes to warn the priest and Olalla but finds that Olalla already knows. He asks her to leave with him once more, but she tells him that she has put her faith in Christ and that she must “pass on upon [her] way alone” (p. 173). Despairing, the narrator leaves her.

Quotations from “Olalla”, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol xxi (London: Chatto and Windus, 1911), pp. 127-74.

“The Treasure of Franchard” (1883)

Dr Desprez and his wife Anastasie live in the country town of Gretz (actually Grez, an artist community that RLS often visited in the mid to late 1870s. For more information, see the page devoted to Barbizon & Grez in the Footsteps section of the RLS Website). The couple adopt a boy, Jean-Marie. Desprez loves Jean-Marie for his spiritual side, as much as he loves his wife for her pleasure in the material aspects of life.

Desprez resolves to teach Jean-Marie his own particular philosophy on life. Despite all of his teaching, however, he cannot make Jean-Marie feel remorse for stealing when he was younger. Jean-Marie insists that he stole only to feed himself, and that God would never think that this was wrong.

One day, Desprez and Jean-Marie go to Franchard. Desprez explains to Jean-Marie that wealth is poisonous, and that Gretz, with its fresh clean air, is a much better place than the evil influences of Paris. Indeed, Desprez had once ruined himself financially in Paris.

He also tells Jean-Marie about the hermits who used to occupy Franchard and how they had concealed their priceless sacrificial vessels somewhere there. When Desprez finds the treasure however, he instantly casts aside all of his advice and “a sort of bestial greed possessed him” (p. 300). His behaviour becomes increasingly erratic and Jean-Marie reminds himself of what Desprez had taught him: “[i]f necessary, wreck the train” (p. 308) – in other words, sometimes it is necessary to take drastic measures in order to save the day.

The next morning, Anastasie and Desprez awake to find that the treasure has been stolen. Admiral Casimir, Anastasie’s brother, arrives, and learning that Jean-Marie was once a thief, instantly accuses him. Jean-Marie vows he will leave unless the treasure is never spoken of again. Terrified that they will lose the boy they love, the Dr and Anastasie agree.

The Desprez’s luck then turns for the worse: their house collapses in a storm and a change in the market means they are ruined. Jean-Marie disappears, only to return with the treasure! Desprez is overjoyed, saying “[h]e is the thief; he took the treasure from a man unfit to be entrusted with its use; he brings it back to me when I am sobered and humbled. These Casimir, are the Fruits of my Teachings, and this moment is the Reward of my Life” (p. 332).

Quotations from “The Treasure of Franchard”, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol vi (London: Chatto and Windus, 1911), pp. 267-332.

Image courtesy of Rare Books and Special Collections, Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina