RLS in Edinburgh | Homes & Haunts | Fictional Edinburgh | Gothic Edinburgh

Stevenson was certainly drawn to the darker elements of Edinburgh’s history. In Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes, for example, he writes:

“So, in the low dens and high-flying garrets of Edinburgh, people may go back upon dark passages in the town’s adventures, and chill their marrow with winter’s tales about the fire: tales that are singularly apposite and characteristic, not only of the old life, but of the very constitution of built nature in that part, and singularly well qualified to add horror to horror, when the wind pipes around the tall LANDS, and hoots adown arched passages, and the far-spread wilderness of city lamps keeps quavering and flaring in the gusts”

(The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol i [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911]).

This section aims to highlight some of the more sinister aspects of Edinburgh’s history that inspired Stevenson, as well as to show how some of Stevenson’s Gothic still lingers in the popular imagination. For example, download a walking tour leaflet for Edinburgh created by the City of Literature here.

The leaflet gives you the “Jekyll and Hyde” tour of the city, showing you the places and events in Edinburgh that may have inspired Stevenson to write the novel.Burke and Hare“There was, at that period, a certain extramural teacher of anatomy, whom I shall here designate by the letter K. His name was subsequently too well known. The man who bore it skulked through the streets of Edinburgh in disguise, while the mob that applauded at the execution of Burke called loudly for the blood of his employer” (“The Body Snatcher”, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol iii [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911] p. 282).Stevenson’s “The Body Snatcher” refers to the infamous Burke and Hare murders in Edinburgh. In the early nineteenth century, medical schools used bodies to teach students anatomy. When these were in short supply, some schools would pay for bodies, regardless of their origins.Body-snatchers, or “resurrection-men” would steal corpses from graveyards and sell them. Burke and Hare murdered their victims and sold them to the anatomist Dr Robert Knox “Mr K___ “ of Stevenson’s story.

Deacon Brodie

“A great man in his day was the Deacon; well seen in good society, crafty with his hands as a cabinet-maker, and one who could sing a song with taste. Many a citizen was proud to welcome the Deacon to supper, and dismissed him with regret at a timeous hour, who would have been vastly disconcerted had he known how soon, and in what guise, his visitor returned”

(Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol i [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911]).

Deacon Brodie’s “double-life” is often considered to be an inspiration for Jekyll and Hyde (1886). Stevenson’s play Deacon Brodie, which he wrote with W.E. Henley, was also inspired by Brodie’s life.

William Brodie (1741-1788) was a cabinet-maker who would come to respectable homes then forge keys and rob them. He was later hung for his crimes.

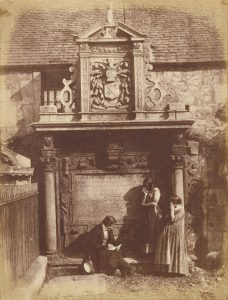

The Stevenson family actually owned a wardrobe made by Deacon Brodie, in their house in Heriot Row. Later, RLS gave the cabinet to W.E. Henley. It is now displayed in the Writers’ Museum (above middle).

Major Weir

“He was a tall, black man, and ordinarily looked down to the ground; a grim countenance, and a big nose. His garb was still a cloak, and somewhat dark, and he never went without his staff” (Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol i [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911]).

Major Thomas Weir and his sister Jean lived between the Castle and the Grassmarket area of Edinburgh. Weir had a thornwood staff and would go to church to lead prayers, but then began speaking of terrible crimes he’d committed: witchcraft, Satanism and incest – all of which his sister confirmed. He was strangled then burnt in 1670 and his sister was hanged. Popular legend says that the ghost of Major Weir still haunts Edinburgh.

The Haunted Mausoleum of Sir George Mackenzie

“Behind the church [Greyfriar’s] is the haunted mausoleum of Sir George Mackenzie: Bloody Mackenzie, Lord Advocate in the Covenanting troubles and author of some pleasing sentiments on toleration. Here, in the last century, an old Heriot’s Hospital boy once harboured from the pursuit of the police. The Hospital is next door to Greyfriars – a courtly building among lawns, where, on Founder’s Day, you may see a multitude of children playing Kiss-in-the-Ring and Round the Mulberry-bush. Thus, when the fugitive had managed to conceal himself in the tomb, his old schoolmates had a hundred opportunities to bring him food; and there he lay in safety till a ship was found to smuggle him abroad. But his must have been indeed a heart of brass, to lie all day and night alone with the dead persecutor; and other lads were far from emulating him in courage. When a man’s soul is certainly in hell, his body will scarce lie quiet in a tomb however costly; some time or other the door must open, and the reprobate come forth in the abhorred garments of the grave. It was thought a high piece of prowess to knock at the Lord Advocate’s mausoleum and challenge him to appear. ‘Bluidy Mackingie, come oot if ye dar’!’ sang the fool-hardy urchins”

(Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol i [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911]).

The lawyer and Lord Advocate George Mackenzie (1631-1691), gained the name “Bluidy Mackenzie” for his persecution of the Covenanters. He also founded the Advocate’s Library in Edinburgh. Local legend suggests that the tomb is haunted.

Plague

“perhaps some memory lingers of the great plagues, and of fatal houses still unsafe to enter within the memory of man. For in time of pestilence the discipline had been sharp and sudden, and what we now call ‘stamping out contagion’ was carried on with deadly rigour. The officials, in their gowns of grey, with a white St. Andrew’s cross on back and breast, and a white cloth carried before them on a staff, perambulated the city, adding the terror of man’s justice to the fear of God’s visitation. The dead they buried on the Borough Muir; the living who had concealed the sickness were drowned, if they were women, in the Quarry Holes, and if they were men, were hanged and gibbeted at their own doors; and wherever the evil had passed, furniture was destroyed and houses closed. And the most bogeyish part of the story is about such houses. Two generations back they still stood dark and empty; people avoided them as they passed by; the boldest schoolboy only shouted through the keyhole and made off; for within, it was supposed, the plague lay ambushed like a basilisk, ready to flow forth and spread blain and pustule through the city”

(Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes, The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Swanston edn, vol i [London: Chatto and Windus, 1911]).

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Edinburgh saw outbreaks of plague. 1645 brought the worst outbreak, when mortality was extremely high.

Stevenson’s Victorian Gothic Today

RLS’s Gothic version of Edinburgh still influences artists today. Ian Rankin, for example, says “I owe a great debt to Robert Louis Stevenson and to the city of his birth. In a way they both changed my life. Without Edinburgh’s split nature Stevenson might never have dreamed up Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and without Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde I might never have come up with my own alter ego Detective Inspector John Rebus”.

Edinburgh has also used the notion of Stevenson’s Gothic to entice tourists. For example, visitors to the city can go to the Jekyll and Hyde pub on 112 Hanover Street, Edinburgh, for an atmospheric drink.